Disruptions are a part of Procurement

As the concepts of globalisation flourished, owners and managers of businesses in developed countries took advantage of an profitable proposition to buy products and intermediate goods from low cost countries (LCC). However, the lure of a low unit buy price meant that additional costs incurred were often not considered.

Extended lead times than planned is an example of additional costs. Recent articles by the UK broadcaster BBC discussed the current problems for importers and consumers in the UK to obtain’ low technology’ household and recreational products from Asia. Delivery times quoted are eight months for recreational goods; five months for kitchen fittings and four months for wooden toys.

The causes of disruptions are by now well-known: COVID19 lockdowns; the rebound in consumer demand (especially on-line ordering); changes in the spending of discretionary income; large retailers in US buying all available northern summer capacity at suppliers. All this with shipping delays and re-positioning containers.

In line with disruptions are increases in costs. In June 2020 a 40ft container from China to Europe cost $2,500; in June 2021 the price is reported as $14,000. The purchase price in the UK for a plastic take-away food container and lid was reported to increase by 500 percent – how much the two price increases are linked was not identified.

Total Cost of Ownership

A myth of globalisation is that low production labour costs means the total cost of the finished product will also be low. However, the costs of accommodating complexity, variability and constraints in global supply chains means that supply chain costs can add up to more than total landed costs.

For example, in the years prior to 2020, retailers in developed countries ordered goods in May-June for the up-coming Christmas and New Year shopping season, with deliveries commencing in August-September. In 2021, ordering has been earlier, adding to factory queues, port congestion and added costs in supply chains (read the blogpost concerning the Lead Time Syndrome). So, disruptions and price increases are likely to continue until at least mid-2023; but, with continuing challenges, it could be much longer.

Also, while publicity about the supply situation has a focus on consumer goods, an additional factor for the medium term is the availability of intermediate goods, including base raw materials. Over the years, production of fabrics and yarns (including ‘technical products’ yarns), conversion of mined ores to metals, basic printed circuit boards (PCB) and many other input items, have been moved to LCC.

All the factors noted indicate that buying decisions need to include many factors beyond the buy price from the manufacturer or exporter, or even the landed cost to your organisation.

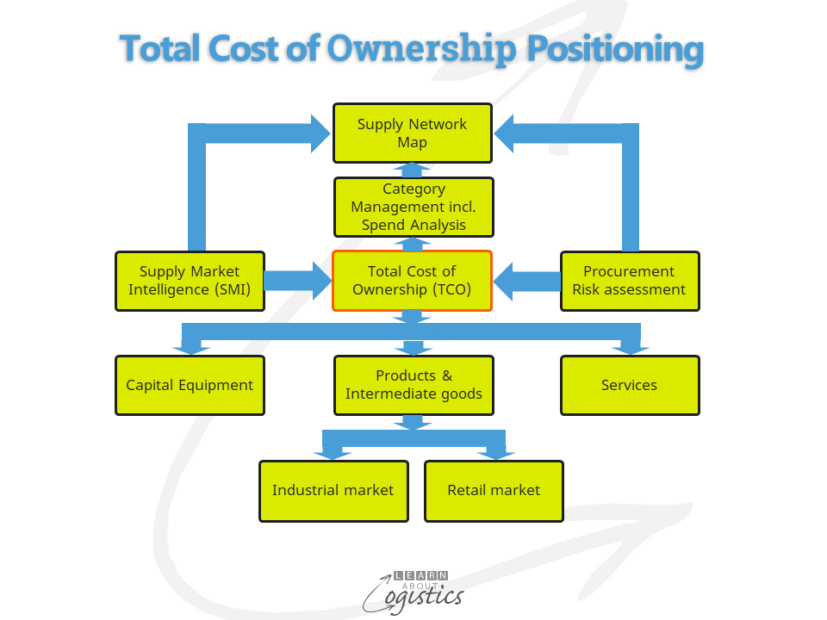

As shown in the diagram above, TCO is an input to the Spend Analysis. As most elements within a TCO are not separately identified in financial statements, the costs will likely be located in multiple locations within the internal accounting systems. These are not designed to extract or consolidate the selected costs, so much detective work will be required. In larger businesses, TCO (along with Spend Analysis) requires a structured application to identify, track, extract and analyse the data.

Elements within a TCO

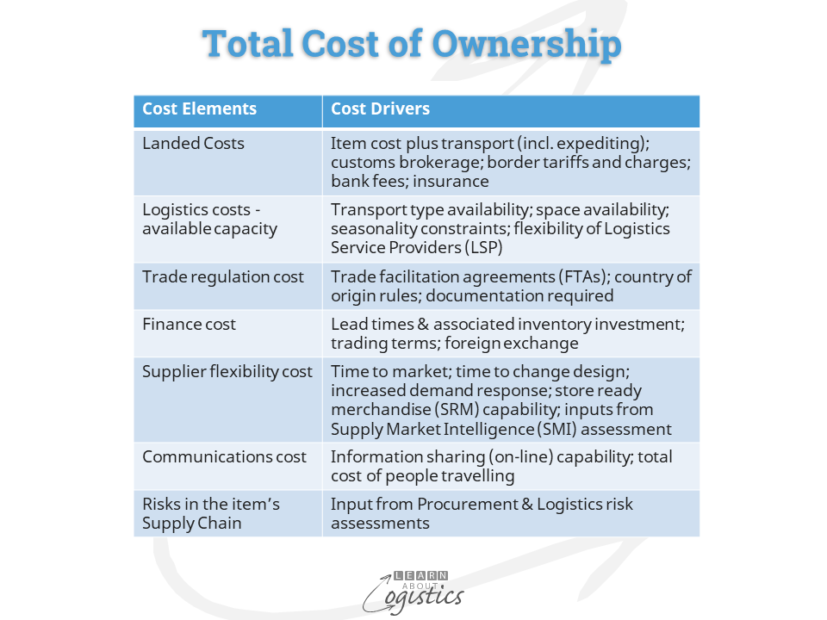

Elements used in building the TCO for an item will differ, depending on the item group, country of the buying businesses and time available for the Procurement personnel to complete the TCO analysis. However, there is a broad range of elements that are common, as noted in the diagram below.

Landed costs are the direct costs of a purchase. It includes the negotiated price of the item and any discounts for volume purchases and on-time payment. If applicable, add the cost of commodity price hedging contracts. Add the cost of transport (including expediting a more expensive mode) by mode and external storage by type, both internationally and domestically; customs brokerage charges (at origin and destination); border tariffs and charges; bank fees and insurance.

In addition to these visible and direct costs are the costs that are not so easily ‘visible’ and identified. These may occur throughout the contract period and should be considered as ‘indirect’ costs of the buy:

Logistics costs

- Transport time (when inventory cannot be accessed) and its affect on the cash-to-cash cycle

- Flexibility (and increased charges) at logistics service providers (LSPs) for changes to delivery schedules

- Seasonal demand and supply fluctuations, plus seasonal adverse weather conditions that may affect availability of transport space and its cost

- Delays through the item’s supply chain, which could result in expedited freight and higher charges required to meet customers’ delivery dates

- Changes to INCOTERMS in contracts

- Inventory costs associated with: postponement, seasonal build, quick response

- Administration costs directly assigned to acquisition and movement of the item

- Disposal costs for ‘out of spec’ items or goods returned by consumers

Trade Regulation costs

- Trade incentives and restrictions: in the buying and selling countries, Include those established through trade agreements (FTAs) between countries or groups of countries. Also, the documentation requirements (and potential penalties for errors) for customs clearance in the importing country

- Import and export costs: additional customs charges charges for examining freight and fumigation charges (if required)

Financial Costs

- Trading terms for payment; trade financing charges – bank fees for ‘letter of credit’ or other types of finance or using the buyer credit rating to enable the supplier to gain credit

- Changes to tariff schedules – which party bears the cost?

- Insurance premiums for assessed additional risk

- Currency exchange rate hedging costs

Supplier and 3PL flexibility costs

- Guarantee re condition of goods on delivery

- Response time for increased orders

- Flexibility (and charges) at the supplier to implement product modifications and enhancements

- Cost of additional services at suppliers or 3PLs which add value to the item. An example is garment hang-tags and price tickets attached at the supplier or consolidation site (i.e. Store Ready Merchandise facility)

- Buyer’s inputs from Supply Market Intelligence (SMI) assessment

Supply Chain IT and Communications

- Supplier’s IT capability (and potential additional costs to the buyer) for interoperability with or interfaces to the buyer’s systems, for information sharing concerning operations planning

- Internet and telephone/fax connections

- Total cost of people travelling to supplier facilities

Risks in the item’s Supply Chain. Inputs from the Procurement and Logistics risk assessments of supply chains and suppliers. They include geopolitical and country risks.

To recognise the Total Cost of Ownership and improve the buying decision for future purchases, Procurement, as part of the supply chain group, should implement the process for identifying and collecting all costs for a product or ‘intermediate goods’. The process should operate on a regular update review timetable.