Terminology is a challenge

A challenge when developing your organisation’s Supply Chains Network Map is the terms to use that describe your intentions. The first part of the challenge is that you will need to build your own dictionary of terms, which is then understood and approved by the senior management group. The second challenge is deciding which of the terms to use that address the objectives of the business.

For example, a term that is popular in articles written by consultants and promotions from software suppliers is Optimisation. To optimize is ‘to make something as good or effective as possible’, so in supply chains, each step in the chain is linked tightly with the next. The Toyota Production System (TPS), also called Just in Time (JIT) is an example, where waste of time and effort is eliminated and no or minimal inventory is held. But there is the challenge of complexity.

Complexity in supply chains

In the twenty years to 2020, the value of trade in intermediate goods between organisations tripled. As functions were outsourced and off-shored and companies divested ‘non-core’ businesses, so the number of suppliers located around the world increased. Within the same period, the expected lead times from customer order to delivery decreased, while the lead time to procure materials and components often increased with global supply.

Concurrently, the pressure on supply chain professionals was to be efficient and to reduce costs – that is to Optimise the supply chains. But while being efficient provides an impression of being in control, the responses to any sort of supply disruption is reactive, due to a lack of information. Typically, Procurement professionals had no knowledge of suppliers at Tier 2 and below in their supply networks. So, vulnerabilities and interdependencies in the supply chains for a business became established. Complex supply networks that have an unknown complexity are the accepted structure.

Because suppliers are typically independent organisations, a disruption in a supply chain is addressed by each organisation in the chain to satisfy its internal corporate objectives. This occurs even though the action taken could provide more problems elsewhere in the supply chain, with little warning of the potential disruption.

Therefore, as a business optimises its assets through becoming more efficient, it also becomes more vulnerable to disruptions – the unknown risks increase, as happened in recent years. Even if companies wish to reduce the complexity of their supply chains, the time to achieve this objective is many years. Therefore accepting complexity means that while optimising selected Nodes and Links in a supply chain may be valid, optimizing total supply chains is not a preferred strategy.

Resilience is the new term

Disruptions in supply chains are not one-off events and will increase in frequency as climate change disasters, geopolitical tensions, protectionism, pandemics, natural disasters and other events occur. A different approach is required, as just identifying the critical vulnerabilities in your organisation’s supply chains is not sufficient to protect the business.

Resilience is the term now being used, the ability of a core supply chain to reduce the impact of disruptions and recover operational capability after disruptions occur. To become resilient requires more of a change in mindset than investments in assets, although spare capacity (including time) at selected Nodes and Links should be a part of the planning system.

The change in mindset is having an Adaptation approach – the preparedness of people with knowledge and capability to quickly respond, plus operating equipment that allows solutions to be implemented quickly. As remaining in business requires that customers have a high measure of DIFOTA – delivery in full, on time, with accuracy, to be resilient requires thinking in terms of Agile and Responsive – but not forgetting Efficient where circumstances allow.

An Agile approach is designed around flexibility for manufacturing products to specific customer orders – Make to Order (MTO and Assemble to Order (ATO), that required flexible lot sizes and quick changeover of equipment. Ideally, it is able to provide customer service that delivers products at the same quality standard and cost, irrespective of demand levels and timing and volatility in supply. A Responsive approach is to shorten the customer order process cycle and can be used where demand for the SKU is steady.

Fit the terms to a strategy model

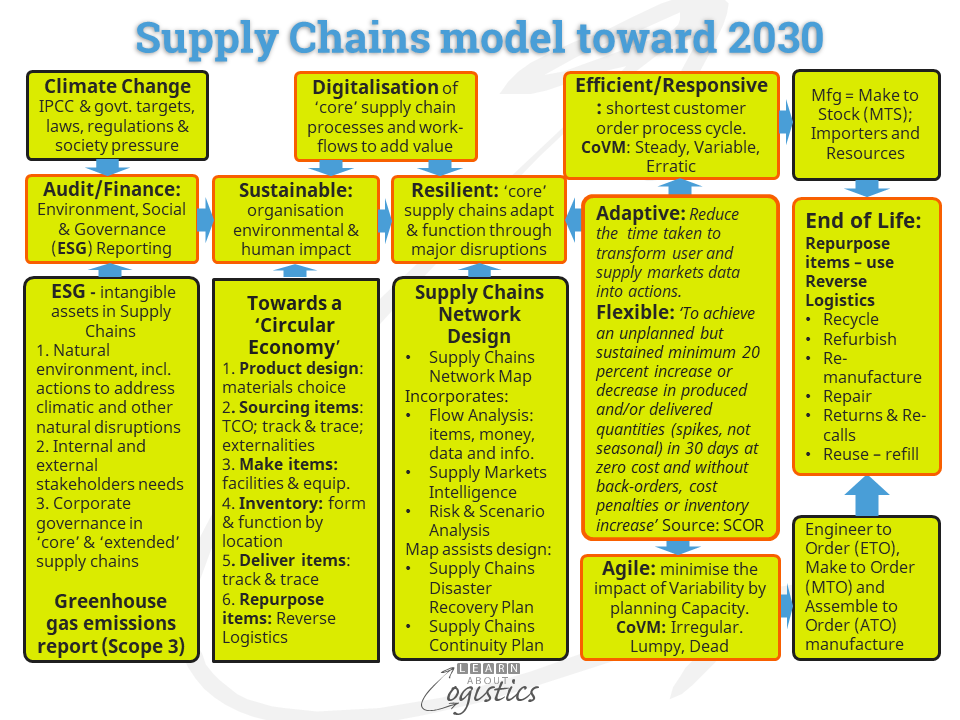

Rather than having the objective of your organisation’s supply chains as Optimisation and Efficiency, think of an Adaptation model, where the current circumstances of the business guide the design. The diagram identifies where the terminology fits into the model.

Sustainable requires thinking of the business as being part of the ‘Circular Economy’ process that includes six main elements from product design to the repurposing of items at end of life.

Resilient (or Resilience): to enable the core supply chains (tier 1 customers back through the business to tier 1 suppliers) to adapt and function through disruptions, there must be access to the Supply Chains Network Design. This incorporates knowledge of the extended supply chains and the Disaster Recovery and Continuity plans.

Resilient supply chains are Adaptive and Flexible. This requires action to change internal flows:

Short term:

- Design from the customer back through the supply chains to identify flows of items, money, data and information

- Identify likely buffers – manufacturing capacity and inventory (structure form and function by location)

- Where are Postponement in production and VMI (vendor managed inventory) options viable?

- Supplier relationships developed to address the flows

Longer term:

- Platform and product line (SKU) rationalisation

- Reduce customer order latency through forecasts using probability ranges and ‘demand sensing’

- Share ‘One Plan’ (clean) data. Aim for master data portability rather than tight integration

Efficient/Responsive and Agile: selection of these processes requires the initial analysis of sales by SKU into CoVM segments , then identifying the planning process required by segment (the supply chains).

End of Life: the process for re-purposing products

When discussing, designing or planning your organisation’s supply chains, it is dangerous to use terminology out of context. You must be able to demonstrate to senior management that the terms are understood and where they fit in the supply chains strategy.