Sustainable Supply Chains.

At the current rate of consumption and disposal of products and with an increasing consumer population, to meet the demand for resource intensive products by 2030 (only 12 years hence!), could require more raw materials than what is available – is this situation sustainable?

David Yeo, a LinkedIn reader of Learn About Logistics, has provided a comment concerning previous blogs on supply chain strategy. He says “Today Supply Chain Strategies should also incorporate the area of sustainability… Supply Chain Leaders must understand the impact of their choice of logistics and how it will impact on the environment and be responsible to mitigate as much as possible…” I agree with David; with some additional thoughts.

- Sustainability can easily be just another buzzword used in business. Without objectives, targets, projects and measurement the term is meaningless

- Implementing a sustainability strategy in your supply chains before the concept has been adopted by the organisation can be a challenge. The board of directors has to agree that the use of materials, energy, water and and generation of waste through the core and extended supply chains will influence the future of the business

- The approach to a sustainable future will require a change of mindset from short-term performance – Return on Investment (ROI)

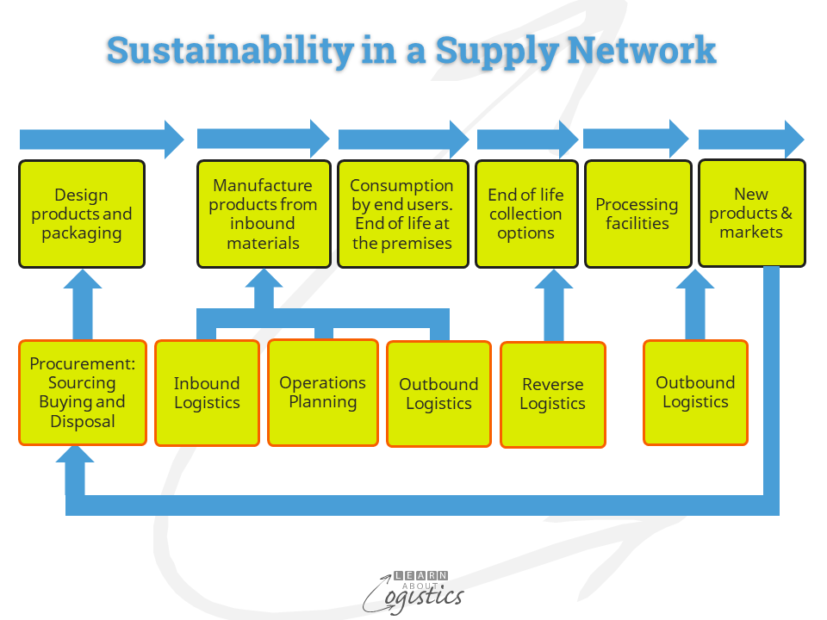

- The supply network is treated as a system which creates value added and incurs total costs of ownership (TCO). To improve both requires a network approach to access knowledge about the most effective practices through each supply chain

The term Circular Economy, promoted by Mckinsey consultants, has similarities to Sustainability. It’s focus is on maximising what is already in use along all points of a product’s life cycle, from sourcing, through the supply chains to consumption, to the remaining unusable products and their conversion back into a new source for another purpose.

Sustainability model

Research organisations appear to have settled on a four level model for the handling of waste across raw materials, packaging, energy and water. Reduce and reuse is the first step; only later comes recycling:

Level 1: Design for waste minimisation – the objective for product designers:

- ‘Avoid and reduce’ total waste approach built into the design of a product

- Set sustainability objectives for all material groups. Where feasible, design the following:

- Build to last: design durable products for customers who are willing (and financially able) to purchase such items.

- Upgrades are designed-in: Instead of replacing the core product, enable customers to add new features, functionality or fashion as they become available

- Set sustainability objectives for all material groups. Where feasible, design the following:

- Develop a Product as a Service (PaaS) business model. Sell performance to customers rather than product ownership:

- Pay for use – customers buy output rather than a product and pay based on use e.g. distance travelled, hours used, pages printed or data transmitted

- Performance Agreement: sell performance, not the product – called Performance based contracts (PCB) or Availability based contracts (ABC). Customers buy a predefined level of operating performance, service and quality and the supplier provides equipment to meet the need

- Established modes of PaaS are renting and leasing

- Design to enable the reuse of materials many times

Level 2: Return products and materials to the economy

Take-back/trade-in/buy-back and then re-market is referred to as ‘ReCommerce’. There are five ‘Re’, which are of interest to Logisticians, through the need to develop the concept of Reverse Logistics:

- Repair – service products to extend useful life

- Refill – replace a function that is depleted more quickly than the total product e.g. refillable packaging or easy to change batteries

- Refurbish – restore the condition of a product at the end of a lease or rental period. Rent or lease again

- Re-manufacture – overhaul a product that has achieved a set number of operating hours or at the time of trade-in; sell the re-manufactured product with full warranty

- Recycle – convert (re-purpose) waste into new products. Waste materials and products are obtained from:

- Rubbish – discarded items, with the different materials isolated for processing. Requires governments to develop markets through buying products made from recycled materials and encourage the community to follow the example

- Recall – faulty product

- Returns – warranty claim

Level 3: Produce energy from waste

Producing energy from waste means that materials are no longer available to recirculate in the economy; however, waste to energy projects can be complementary to recycling in processing genuine residual waste. For example, to achieve a high level of return into the economy, sorting centres separate contaminants from recyclables and the contaminates are burnt for energy.

Level 4: Dispose

Send waste to landfill is the least desirable option.

Sustainability of Supply Chains

Although the word Logistics is proclaimed across many trucks, Logistics is more than transport and Supply Chains is more than Logistics. Logistics Service Providers (LSPs) that wish to stay in business should be implementing their own sustainability strategy within their business plans. So, within a Supply Chain strategy for a shipper, initially address the areas where your organisation has operational management authority. Evidence of success can then be shown to suppliers and other businesses as the basis for negotiation about sustainability.

An initial question for your sustainability strategy is ‘What is the objective behind supply chain sustainability decisions’? Examples are:

- Reduce energy consumption within the supply chains

- Collaboration along the supply chains

For each supply chain function, some factors to consider are:

Procurement – sourcing and buying renewable, recyclable, or biodegradable materials as substitutes for new inputs:

- Product life cycle: There are points in the life cycle, such as re-negotiating a contract for ongoing supply of a material, when it is cost effective to implement sustainability actions

- Sourcing: Incorporate evaluation criteria related to materials, packaging or processes to meet sustainability objectives

Logistics has two elements:

- Distribution, warehousing and storage: Reduce the energy and water resources required per unit of sale

- Transport management: Evaluate the most effective transport options by mode concerning: density of the product; stowability/stackability; handling; liability and return trip capacity. Factors to consider:

- Future fossil fuel costs – global politics can quickly change pricing models

- Congestion costs by transport mode

- The emphasis of logistics changes from physical movement to information exchange and analysis

Developed countries have done well in the linear economy of ‘take, make and dispose’. However China, the world’s biggest re-processor of materials, has done the developed world a favour by banning the import of low-quality, contaminated and hazardous waste materials. This has brought attention to the need for countries and companies to be responsible for their own waste and therefore to produce less of it. The challenge will not go away.