Increasing tariffs on goods.

International Trade is in the headlines, with dire warnings concerning increased import tariffs, leading to rising protectionism and a slowing of world trade. But, in making the forecasts, commentators may not always understand how global supply chains actually work.

Globalisation, International Trade and International Business are terms commonly used when discussing trade in goods and services across the borders of countries. These terms originated in the study of economics and therefore discussion tends to concentrate on aspects of government and business policy, rather than supply chains.

Currently, the reported trade balances of countries are based on the gross commercial value of the goods and services as they depart and enter a country. However, these reported trade balances do not capture the actual situation of business and economic relationships in international trade.

A picture of international trade

The networks of supply chains have changed how International Trade is conducted. Materials, parts and components (and associated services) can now move across multiple national borders in order to produce a final product, which is then exported. This is noticeable for consumer durables, automotive, machinery and instruments, some apparel and footwear. From a logistics view, the scenario unfolds as:

- Multinational corporations (MNCs) have accounted for much of the growth in world trade; in part, due to exploiting labour arbitrage. This refers to identifying the total cost differential between producing identical goods in a high and low labour cost market and capitalising on the difference by moving operations to the low cost market

- In developed market economies, MNCs that buy and sell products through their subsidiary businesses may account for over three-quarters of home country trade flows. In countries such as Australia, which encourage inbound investment by MNCs, more than 50 percent of the country’s international trade is between related parties

- The trade between related parties is often in the form of ‘intermediate goods’ – that is parts, components and sub-assemblies. They can be more than half of the goods imported by the large OECD economies and up to three-quarters of imports for larger developing economies, such as China and Brazil

- However, in official trade records, the country at the final stage of manufacture is considered as having made the total product. An extreme example is an electronic item, exported with a total value of U$150, which is assembled from U$146 of imported ‘intermediate goods’. Only U$4 of value is added in the ‘export country’ through assembly, final test and packaging. More common examples have an added value of between 20 and 30 percent

- Countries tend to import intermediate inputs from other countries in their region. This is due to delivery time constraints, transport costs and supplier production networks. The supply chains of region economies in Asia, Europe and the Americas have therefore become more intertwined

- It was considered that by 2009, trade in intermediate goods made up about two-thirds of intra-Asian trade and is estimated to now exceed 70 percent. Final assembly of a product occurs in a country designated by the brand company as the supply hub for the product; ultimately shipping the finished product for global sale through retail outlets. Examples in Asia are (in addition to multiple products exported from China): vehicles from Thailand, refrigerators and washing machines from Thailand, air conditioners from Malaysia and televisions from Malaysia and Indonesia

- This means that the supply hub in Asia for a product can be changed, at a relatively low cost, to a country not affected by increased tariffs. The cost will be to build an assembly operation (or modify the outsourced contract), hire and train staff and change the supply links (but not the nodes) in the product’s supply network. As the import cost does not change and consumer demand remains the same, imports are unlikely to decrease as expected

International Trade Logistics

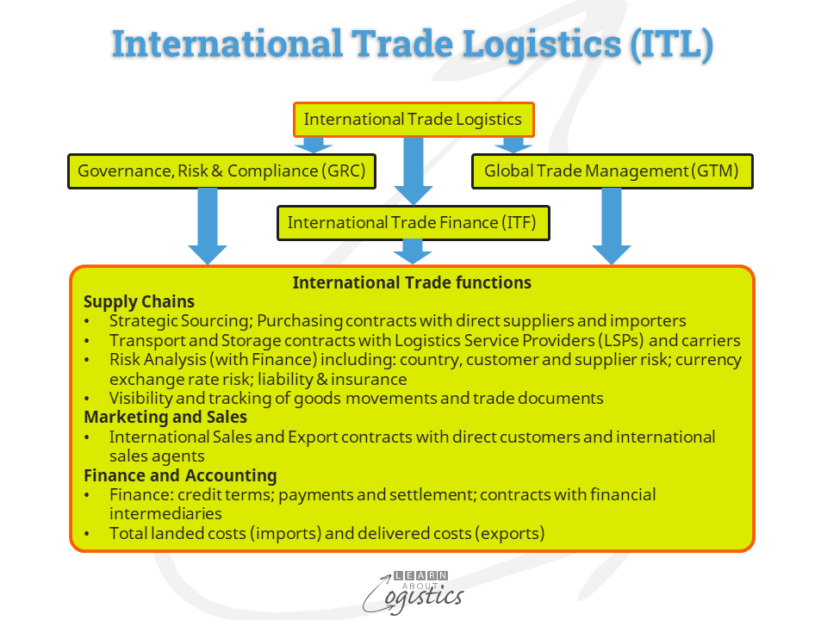

As supply chains are at the core of global trade, Logisticians need to understand the vagaries of international supply chains. Logistics in an international environment is called International Trade Logistics (ITL). A definition is “Management of asset and non-asset sourcing, manufacturing and distribution across international borders to meet demand requirements of an organisation’s customers”.

The diagram shows that ITL incorporates three modules:

- Governance, Risk and Compliance (GRC), to meet the requirement of countries for detailed and accurate documentation concerning cargo movements. The outcome of non-compliance can be high penalties and delays in the movement of goods. GRC within an ITL environment is:

- Governance – Ethical management of international relationships by a company’s executives and managers

- Risk – Identify and mitigate risks that can hinder an organisation’s international operations

- Compliance – Conformance with regulatory requirements for international business operations and practices

Compliance addresses the regulations of exporting and importing countries; for example:

- Product classification of the goods using the Harmonised Tariff Schedule (HTS), developed and maintained by the World Customs Organisation

- Source (countries of origin) and final destination details

- Use of preferential trade agreement (often referred to as free trade agreements (FTAs)

- Security screening

2. Global Trade Management (GTM), which is the design and flow of documentation (electronic and physical) in the global transaction life cycle across order, logistics and settlement activities. In contracts, it covers areas such as:

- Terms of delivery (Incoterms)

- Carrier booking and communications

- Shipment documentation

- Visibility of shipments

- Co-operation and co-ordination through supply chains

3. International Trade Finance (ITF) requires an understanding of how global finance products map to the supply network and how this can affect business processes and cash flow needs. It includes areas such as:

- Co-ordination with financial firms for letters of credit (LCs), open account financing or newer trade financing options

- Invoicing and settlement, including Factoring and commodity futures markets contracts

- Calculation of duties and tariffs; fees and taxes; duty drawbacks

- Customer credit risk

- Cargo insurance and carrier liability

There are multiple locations for cross-border materials movement, compliance monitoring and customs clearance – all being a source of delay. So, which Supply Chain professional in your organisation is responsible for ITL – at the local level, regionally and internationally?