Where is your supply chain organisation?

There is not a correct location for supply chains within an organisation structure or model. The core supply chains organisation structure should be the same for any entity. However, where the supply chains fit in the overall organisation will differ, depending on a number of factors.

The post Organisation to improve your supply chains performance discussed the organisation structure of your core supply chains; that is, the management of relationships and operations concerned with inbound, internal and outbound movements of materials and their associated services. The core functions are: Procurement, Supply Chain Planning and Logistics. In addition and depending on your organisation’s business model, the supply chains structure may also include: Supply Chains Finance and Legal, tactical Marketing and Sales and Supply Chains IT.

But, where does your supply chain organisation best fit within the overall organisation and its business model? Companies operate with their own view of how they relate to their markets; therefore, companies in the same industry can operate in quite different ways, including their supply chains.

At one extreme, business can have common strategies, products and organisation at all locations of the business. At the other extreme is to recognise differences – regions have unique characteristics which require local knowledge to address. This requires a structure of independent operations with local management and even a board of directors.

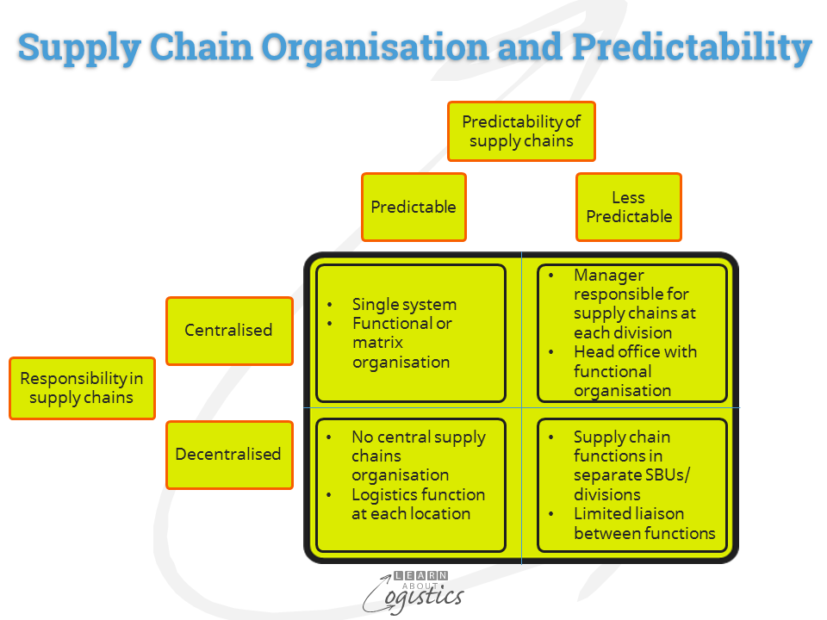

An approach to fitting the Supply Chains group into the organisation model is to consider two factors that affect the extent of supply chain decisions. The first is the level of predictability in the supply chains and the second is where in the organisation is responsibility for supply chain decisions.

Predictability and Responsibility in your supply chains

The predictability of supply chains is governed by the supply and sales markets in which your business operates. For example, where infrastructure for the movement of materials is large (capital intensive), such as from mines to loading ports, the supply chain decisions are more predictable. In this scenario, the organisation is more likely to be structured functionally, with department efficiency and cost control as drivers.

Compare this with companies operating in the fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) and consumer packaged goods (CPG) sectors. Here there is less predictability, with decisions concerning supply chains made with reference to capacity at component suppliers, contract manufacturers, logistics service providers (at both source and customer locations), sea and air ports and retail outlets. This requires planning to be on a more integrated basis, rather than in functional silos.

Responding quickly to changing customer requirements requires a focus on managing processes rather than functions. Processes are a sequences of activities that create value for customers and cross-functional, typically managed through the activities of cross-functional teams. Each team comprises specialists and a team leader as the integrator with other teams, to achieve market and customer based objectives, such as ‘delivery in full, on time, with accuracy (DIFOTA).

Responsibility in supply chains is a reflection of the extent to which an enterprise is centralised or decentralised. Considerations are:

- Culture of the organisation: the level of autonomy and influence allowed for business units; also the willingness of senior management to mandate a policy or a process that covers the total business

- Centralised supply chain model: this is best suited when the products generated from each business unit are similar and therefore require similar planning, buying, handling and transport services. Under this model, the central supply chains group makes decisions and exercises control over relevant activities throughout the organisation. For example, Procurement leverages suppliers through total corporate spend and implementing standard sourcing, buying processes and technology decisions

- Decentralised supply chain model: this is best suited for organisations with divisions that operate as independent entities, with limited sharing of information. In each division, there is a high degree of autonomy and control over planning, sourcing, buying and logistics processes

- Federal supply chain model (also called the centre-led or strategic and staff model). Both centralised or decentralised structures have limitations, therefore the Federal structure is a ‘middle way’. Here, the central supply chains group has its focus on strategy planning, strategic commodity sourcing and corporate logistics and shares knowledge about the organisation’s supply chains and best practice. It leaves tactical decisions and operational execution to the individual strategic business units (SBU), but the centre consolidates transaction data for analysis of supply chain performance. An adaptation of the Federal model has an organisation’s supply chains model based on major product markets, marketing channels or customers.

- Tax effective locations for financial transactions is also an adaptation of the Federal model. For example, companies operating across borders may establish a supply chain subsidiary company in a low tax (but not low wage) country; here, strategic demand and supply planning decisions are made, but no goods physically pass through that jurisdiction, just sales invoices and purchase orders. Factories are located (often through 3rd parties) to operate as fee-for-service contractors, with the supply chain subsidiary company providing materials and components and advising the destination of finished items. This could be a bonded facility in a low tax location within a region, which distributes goods to sales entities in countries that hold minimum inventory and receive items ‘to order or as required’.

The supply chain model for your enterprise will therefore depend on the business, industry and cultural setting. To match the supply chain model to the changing business and industry situations, senior management should consider the following questions:

- What decisions are critical within the organisation’s supply network?

- Where in the supply chain organisation model and structure should these decisions be made?

- Do the people expected to make the decisions have sufficient authority?

As business models change, so will supply chains. However, this discussion has considered the base policy settings which affect the organisational variables for your supply chains model; these need to be reconciled with your organisation’s business model.

Best wishes to all readers for the New Year. The summer holiday season in Australia has commenced, so it is time for the beach. The next blogpost from Learn About Logistics will be published on January 11, 2017. For those using Twitter, there will be an opportunity each week to read an earlier blogpost.