Slowing sales and rising inventories

Reports concerning retail product sales in various countries indicate a slowing rate of sales growth as consumers are again able to access services. For all businesses in product supply chains, this will provide a challenge for managing inventories.

An example of the challenge is a major online non-food retailer in Australia which has experienced a decline in its Q1 2022 sales. The company had “geared up for continued elevated sales growth in line with previous quarters”; that is, the future was expected to be like the past, plus some more – always a dangerous assumption! They explain that the business “misjudged the level of ongoing consumer demand and has been left with a glut of inventory, forcing the business to pay higher warehousing costs and aggressively discount stock”. In the UK, the volume of inventories held by manufacturers has risen sharply, but without overall business activity rising at the same rate. In the US, there is a growing concern that as consumer spending reverts towards the pre-COVID trend, both physical and online retailers will be left with excessive inventories.

As government financial stimulus programs are stopped and inflationary pressures increase (but without the required increases in wages), consumers are likely to quickly rebalance their spending towards essentials. So, for business in discretionary spending sectors, the reduction in sales could occur quickly. However, these companies may have products on order where the delivery date has been delayed due to supply chain problems. Also, orders that have been accepted by suppliers are in process and yet to be shipped. So inventories could increase.

In addition to increased inventories, there will be increased inventory holding costs, putting pressure on Logisticians to reduce inventories. But there are few remedies – discounting prices and selling surplus stock to clearance businesses are but two. This may eventually reduce the rate of price increases, but shipping, handling and storage costs are likely to remain at high levels for some time. Container shipping companies are increasingly better at controlling capacity by route, while investments at ports will take years to implement and warehouse vacancy levels are generally low.

So, is having increased cycle stock and safety stocks the correct decision for your business to address disruptions within global supply chains?

- COVID19 has not gone away, as shown by recent actions in China and new variants could appear at any time, or old variants re-energise, as is occurring in South Africa;

- disruptions through supply chains are likely to take at least another twelve months to resolve and that was without new disruptions, such as caused by the Russian invasion into Ukraine and

- what if retailers reduce future orders, which affects all upstream suppliers with inventories?

There is not a ‘right’ decision about the level of inventories that work best for your business. There are analysis processes to help, but it requires the knowledge and skill of a Logistician to evaluate inventory by location through Tiers of supply chains. Copying what other businesses are doing will not help and may make the situation worse.

Inventory is a buffer between demand and supply

There are two buffers available in supply chains to balance the difference between demand and supply. They are inventory and capacity in manufacturing and distribution. However, the strategies of outsourcing manufacturing and obtaining a high utilisation of production assets has meant that the opportunity to use capacity as a buffer has been generally lost. As a result, inventory has become the critical buffer to absorb the variances between demand and supply.

With this level of importance attached to inventory, there is a need to understand how (and why) your organisation’s inventory is structured and the multiple reasons why inventory can increase, to discuss with Finance and Marketing.

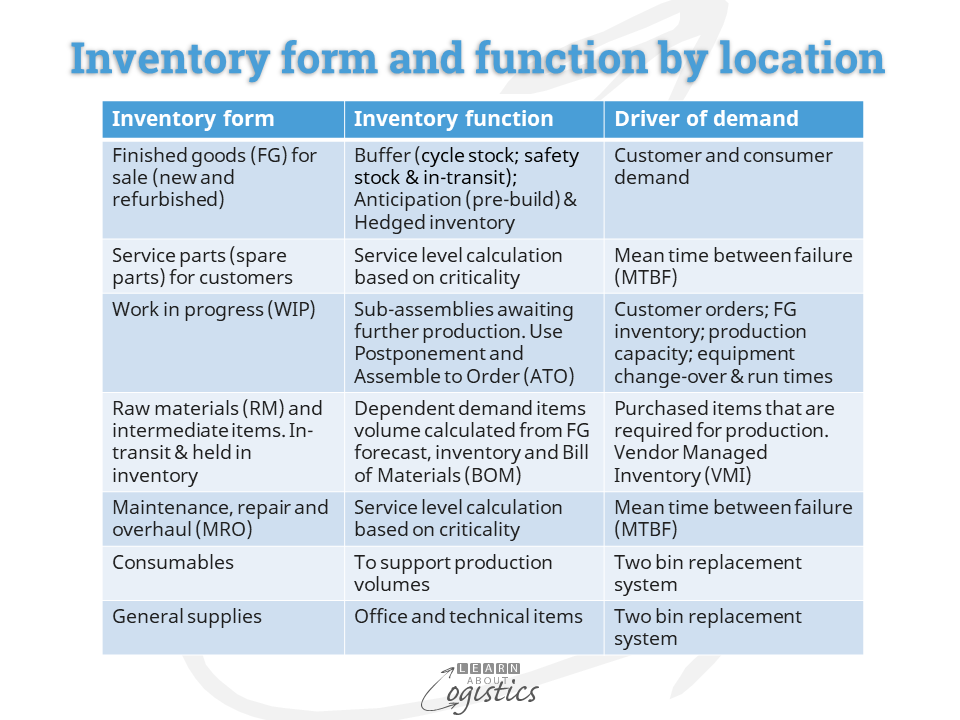

The diagram illustrates the structure, based on the ‘form and function’ of inventory for each location in the Supply Chains Network Design map. This will identify the ‘where is and where should be’ locations for the different inventories. Examples of locations are: at supplier premises; at a 3PL or other Logistics Services Provider (LSP) for intermediate items; in transit (i.e. floating warehouses); at company owned or leased premises; at 3PL or other Logistics Services Provider (LSP) for finished goods; at customer location (your products provided as VMI).

Procurement can identify how the ‘terms and conditions’ (T&Cs) in supply contracts influence the ‘form and function’ by locations. Examples are VMI terms; full truckload requirements and the maximum stacking height of pallets.

Increases in Inventories

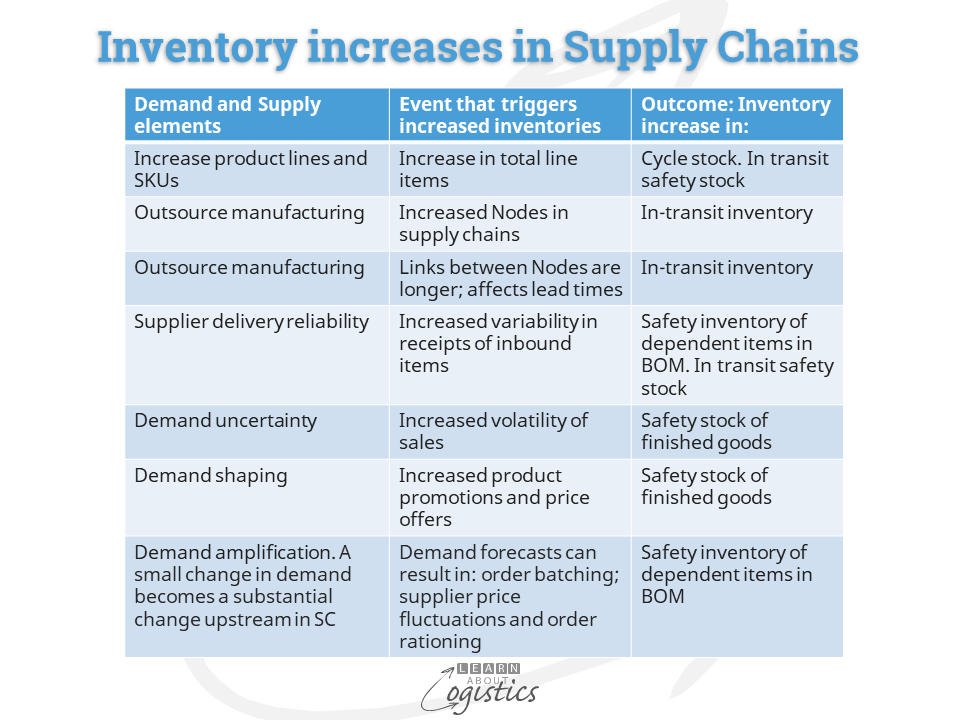

It is not the numerical increase in inventories that is important (although it is typical of performance reviews in organisations) but rather the reasons for the increase. The table below illustrates the possible circumstances surrounding increases in inventory.

Increased volatility in demand and supply markets since 2020 has been the main cause of inventory increases, as many companies decided to add more ‘just in case’ safety stock. But is that amount too much or insufficient? To obtain the answer, start by identify the long tail of items in the product portfolio. The urgency by Marketing to provide ‘consumer choice’ by extending product lines through alternative options or ingredients or additional pack sizes, results in companies usually having many ‘rats and mice’ items in the portfolio. These have insufficient (but volatile) sales and take up space in warehouses.

As the number of line items increase and changes occur in product markets or consumer preferences, more of the Demand Plan input to the Sales & Operations Plan (S&OP) cannot be forecast. Calculating the coefficient of variance (CoV) identifies the SKUs which can be forecast. But the next question is what to do about the SKUs that cannot be forecast. Be prepared that gaining agreement to eliminate SKUs from a product portfolio is a long and difficult task for Logisticians.

As the number of SKUs increase and outsourcing to low cost countries (LCC) occurs, inventories increase in:

- Cycle Stock (the inventory required to cover sales for the production and distribution replenishment cycle of an item)

- In-transit inventories (also called ‘floating warehouses’) and

- Safety stock for inbound items, to cover longer freight lanes and delays in ocean transport

The calculated inventory within a period for a business is a physical identity, similar to Flows (of items, money, information and data) through supply chains, identified in the Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) process. Inventory quantities are calculated based on the customer service policy and the Supply Chains strategy, not on a financial target. If the calculated figures do not meet financial expectations, then address the underlying drivers used in the calculations. This is often a very difficult concept for Finance to accept, but needs to be achieved for inventory management to be real rather than a just a title.