An ERP system

Because you can do something does not mean that you should. This applies to how you implement ERP systems and SNAP applications, which are predominately for use in planning and controlling supply chains.

Most often encountered in business organisations is one or more enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, which contains modules designed to ‘integrate’ operational plans, resources, money and people. Depending on the software supplier, an ERP system will be either a standard package, or a core accounting module with additional modules, specified to meet an organisation’s requirements.

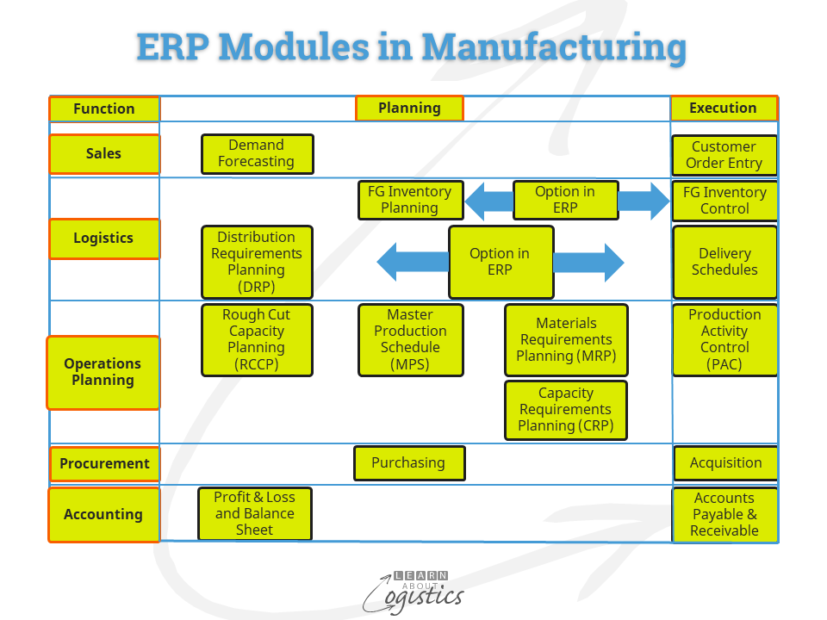

For a manufacturing company, the traditional ERP system modules are structured similar to the diagram. Service areas such as HR have been omitted.

ERP systems are typically designed to address two different operational types:

- Discrete products that are in a solid form and can be disassembled into their discrete components, such as electronic items, motor vehicle components and furniture

- Manufacture products through a more continuous processes which are in a liquid, semi-solid or powder form – such as foods and beverages, pharmaceuticals, paints, chemicals and plastics

Why are SNAP applications required?

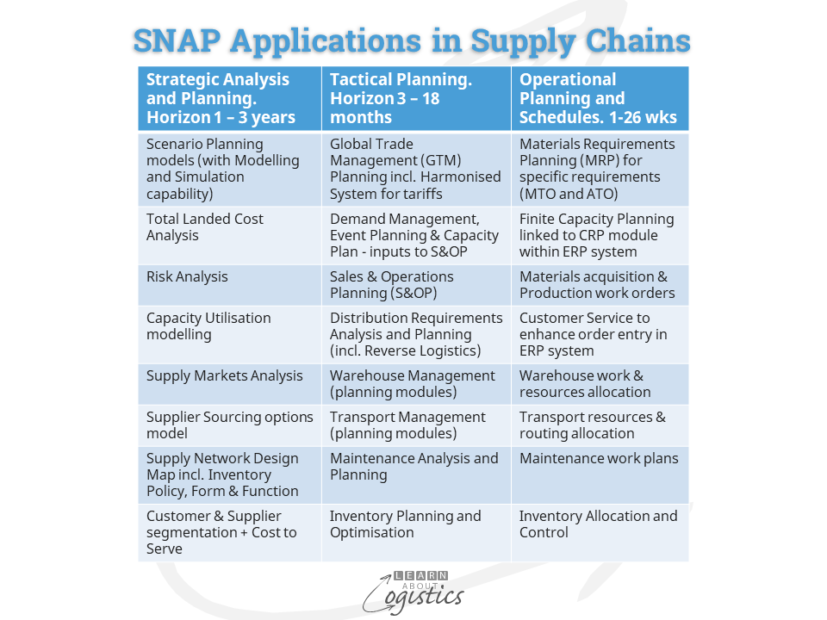

Comparing the above ERP system diagram with the Supply Network Analysis and Planning (SNAP) diagram below, an ERP system does not contain any strategic supply chain analysis and planning modules – ERP is mainly concerned with resources planning.

SNAP applications are also required because ERP systems do not address the more complex analysis and planning needs of current supply chains; listed under the Tactical and Operational Planning columns in the above table. These applications are required due to increasing complexity, variability and constraints in supply chains, which leads to greater Uncertainty in a Supply Network and subsequent Instability in the system processes. Examples are:

- Using standard ERP processes, organisations are less able to quickly identify changes in demand and supply markets and align the response of their supply chains.

- Demand latency: the increasing time between when an item is sold to an end user to when the order for replacement items and materials is processed

- The further up a supply chain and sales orders from customers are less a representation of actual end user demand

- Supply Chains Planning time horizons must be used to avoid nervousness in planning processes

- Increased SKUs to address niche markets and an increasing requirement by end user markets for greater responsiveness (i.e. shorter lead times), means the demand profile for an organisation’s products can become more ‘intermittent’ and ‘lumpy’

- The cycle and safety stock required under intermittent and lumpy demands (a skewed demand distribution) will be higher than under a normal distribution

- The traditional inventory techniques of calculating finished goods safety stocks based on a normal demand distribution is limited to only high and consistent selling products

In addition, to measure the performance of supply chains, there are three main operational objectives, which ERP systems do not address:

- Delivery Performance – the probability of delivery ‘in full, on time, with accuracy’ (DIFOTA)

- Providing Availability of items for customers through Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) and

- Minimising Uncertainty (risk) using calculated inventory ‘form and function’ and capacity buffers through the supply chains

Efficiency and Effectiveness in supply chains

It is too often assumed (without much evidence) that a tightly integrated ERP system makes vertically structured departments more efficient. This is in opposition to the aim of supply chains, which is to provide more effective horizontal flows of items, money, transactions and information.

To achieve more effective horizontal flows requires that demand and supply requirements are not managed as a process undertaken by functions. Instead, the focus of the horizontal flow process commences at the customer (or better, at the end user), back through the organisation and out to suppliers. Demand for products is not forecast by sales, but planned (based on collected and collated data) within the Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) process. This provides guidance for operations planning and procurement decisions across an organisation’s departments.

Transactional data which is internally generated from an ERP system may currently provide more than 60 percent of data inputs; however, the balance of data inputs will increasingly come from:

- end user market and distribution channel data

- use of streaming data – an example is a retailer streaming sales of a supplier’s product sales by geographic area

- accessing data from sensors

- using analytics to access information from large data sets (i.e. big data lakes)

Since the early 2000’s, improved application tools, operating systems and ‘cloud’ computing have influenced a change in thinking about the management of applications. Also, articles and conferences promote the vision of supply chain planning applications, such as warehouse management systems (WMS) being ‘integrated’ into ERP systems.

Integrating and Interfacing software applications

The effectiveness of planned supply chains has become more important to organisations and therefore the need for additional SNAP applications, which address the requirements of supply chain professionals.

Of course, the development and use of SNAP applications has prompted suppliers of ERP systems to ‘integrate’ popular application types into their ERP products. However, if the additional applications have been acquired through a business takeover, the ‘integration’ could actually be ‘interfacing’.

The difference between the two approaches is:

- Integrated applications use the ERP database; therefore data synchronisation is not required

- Interfaced (or connected) applications maintain their own data structure and therefore need to synchronise with the ERP database. Although interfaced applications may be more comprehensive in design and capability, they can be more expensive to support

Because companies are outsourcing functions and changing their business model and structures to address market needs, the comprehensive ERP system, with its fixed and integrated functionality, can become a hindrance to the changes.

As ERP systems hold a dominant position in the IT market, they are unlikely to change in configuration and are unlikely to be replaced. However, ERP system can be re-positioned to be the transaction backbone of an organisation. The system would contain an audit trail of sales orders, purchase orders and payments, plus accounting, production and people data and a reporting capability.

From a supply chain perspective, an organisation would have an ERP business platform and a Supply Network platform, which contain the SNAP applications. Analysis and Planning of supply chains would happen within the interfaced (or connected) specialist SNAP applications located in-house, at a data centre or at an LSP.

In this scenario, the SNAP applications access the required base data from the ERP backbone, download additional data, planners complete the task and upload the solution to the ERP backbone for consolidation and access, based on the users ‘need to know’.