Skilled or knowledgeable

The previous blogpost discussed the appropriate opportunity to invest in ‘new’ technologies for supply chains. But what skills are needed to buy, implement and use the technologies?

A recent paper titled 21st Century Procurement Skills strongly emphases digital skills, but is this the correct approach? The author identifies the core skill required as “Solid, explicit digital knowledge…”. But, what does this mean? The author’s next skill requirement is “Digital fluency is key to ensuring the best use of innovative tools”.

The author therefore contends that, based on dictionary definitions, digital knowledge of Procurement professionals (and by implication all professionals working in supply chains) should be ‘dependable, sound and unambiguous; with the confidence to use digital terminology. However, this does not define the width and depth of the required digital knowledge and fluency.

Is an academic or professional IT qualification required? Or should a professional, as part of their on-going learning, read books and on-line articles concerning IT and its role in supply chains; also attend relevant workshops and conferences and invite representatives of technology suppliers to visit for a coffee and chat.

Consider these questions within a framework concerning to what extent should a professional in one area of expertise rely on their acquired knowledge of another discipline. The challenge with a changing discipline such as IT is that explicit knowledge can quickly become outdated, if not continuously applied.

To be effective, Procurement professionals should not be so ‘knowledgeable’ in any one technological area that they fail to ask ‘dumb’ questions of their suppliers; the outcome is that both parties assume the Procurement professional already knows the answers. Going the other way, there have been examples of technical people, when buying IT equipment and applications, failing the task due to a lack of knowledge concerning the principles and processes of Procurement.

Role of technology

It is unfortunate that technology appears to becoming the de-facto driver of business – ‘systems driven’ and ‘IT focused’ are too often seen in annual reports, with the emphasis on ‘IT solutions’ to business challenges.

A possible outcome from this approach was recently highlighted by a demand of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) for 36 banks, insurers and superannuation funds to self-assess and report their ‘non-financial risks’.

Based on these reports, the Authority stated that financial firms “will need a real focus on the root causes (of problems with customers), including: complexity, unclear accountability, weak incentives and cultures that are too accepting of the gaps”. Only three firms agreed to publish their results, with one report stating “…there is a propensity to believe that ‘more is more’: more analysis, more information, more documentation, more iteration of papers, more sign-offs, more meetings, more policies, more frameworks, more ’stuff’…Many employees resign themselves to complexity as the natural state of affairs and their response to that complexity is often to wrap more complexity around it – potentially adding risk in the process”.

This business states that it has a “key focus on the modernisation, simplification and automation of underlying platforms and technology”. Two thirds of more than $A2b of technology spending in 2018 was on system upgrades, digital transformation and innovation. Yet the outcomes have not aligned with the intention. Could complexity creep into your organisation’s supply chain function, with IT easily available to handle the ‘more is more’ of stuff?

Downstream and Upstream activities

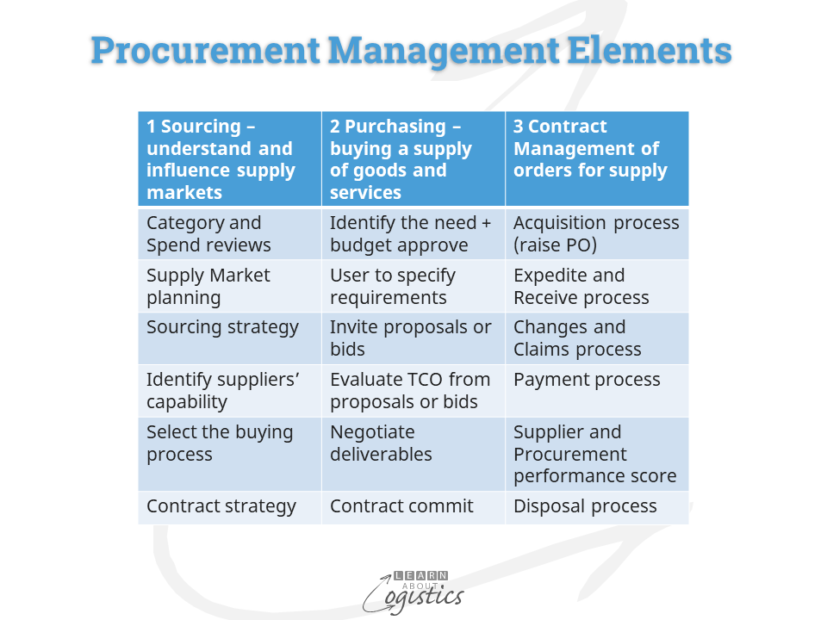

Commitment to a contract signals the commencement of activities for using the items that have been purchased. These can be termed ‘downstream activities’, with their main feature being they are routine and repeatable; therefore can be standardised and computerised. The diagram lists the main ‘downstream activities’ in column 3: Contract Management.

Prior to contract commitment, the activities are all required to ensure the organisation obtains ‘value for money’ in its relationships with supply markets. These are termed as the ‘upstream activities’, listed in the diagram under column 1: Sourcing and column 2: Purchasing.

These activities are less structured, therefore require skilled people to plan, implement and interpret the activities, depending on the prevailing circumstances. While the use of computer based scenario models and data analysis are important, upstream activities do not lend themselves to a standardised ‘systems’ approach.

But, it remains too typical that the focus of Purchasing departments is on ‘downstream activities’ – addressing today’s immediate and urgent problems, such as disputes with suppliers concerning deliveries, quality, price adjustments and other contractual terms. Because it is readily available (especially via the Cloud), IT applications can be used to assist with addressing these urgent problems; but are they important?

Could it be that the ‘downstream activities’ workload results from the lack of investment in ‘upstream activities’? To up-skill from a Purchasing department to a professional Procurement function requires the work ratio to change from about 3:1 in favour of ‘downstream activities’ to a ratio of 2:1 in favour of ‘upstream activities’. This will result in Procurement professionals changing the emphasis concerning IT and technologies.

In reference to the above finance industry report, the chief information officer said “…the concept that an IT person doesn’t understand the business they work in is why that has to end really quickly. And similarly, the concept that someone can work in a business and not fundamentally understand the IT that supports their business, again I think is something that won’t last as well”.

So, what IT skills should professionals working in supply chains possess? It is unlikely (and not recommended) that supply chain professionals will engage in systems design or programming, so a formal academic qualification could be too much – unless you think it will secure your next job!

However, as an insurance policy, employ within the supply chain function a ‘superuser’ (most likely a planner) who you can trust, This person will have a deep understanding of how the current and proposed applications in Column 3 of the diagram actually work and a willingness to investigate the requirements of IT for ‘upstream activities’. In internal and external negotiations, they will provide the bullets, but you will fire the gun.

The blog-post Link Commercial and Control Systems in Supply Chains discusses the level of understanding required to negotiate commercial IT and technical/control processes and requirements in an operational planning and distribution environment.

Using the keywords in the blog-post, map the personal learning you require to search for information and drill down to a level at which you are comfortable. This should provide you with sufficient understanding and confidence when discussing IT and technologies with other executives and supplier sales representatives.