Pioneer work in supply networks.

The concepts and rules by which Logistics functions within organisations are much like a wheel. At the hub are the foundations by which the discipline and associated IT applications work and at the rim of the wheel are ‘new’ discoveries. These are often adaptations of established concepts, typically with a different name.

One of those who built the foundations was Jay Forrester, who recently died after a long academic engineering career. He was an early pioneer in the development of system modelling, with his body of work called System Dynamics. When applied in industry he called it Industrial Dynamics; the title used for his 1958 HBR article and 1961 book, to study “…the behaviour of industrial systems to show how policies, decisions, structure and delays are interrelated to influence growth and stability”.

He identified that an organisation was part of a system; today called a Supply Network, which has its own dynamics by which nodes respond to actions of other nodes – without a system controller (so, a Supply Network is a Complex Adaptable System or CAS). His thinking on the topic developed through a study within a General Electric (GE) factory that experienced fluctuating levels of inventory and employment. Senior management wanted him to identify and measure the external factors causing the problems. However, discussions with operation managers and investigation identified that the fluctuations were actually caused by internal policies and rules concerned with inventory planning and control. He wrote:

“Typical manufacturing and distribution practices can generate the types of business disturbances which are often blamed on conditions outside the company. Thus random, meaningless sales fluctuations can be converted into annual, seasonal production cycles by the action of feedback. Advertising and price discount policies of an industry can similarly create two and three “rogue” sales cycles.”

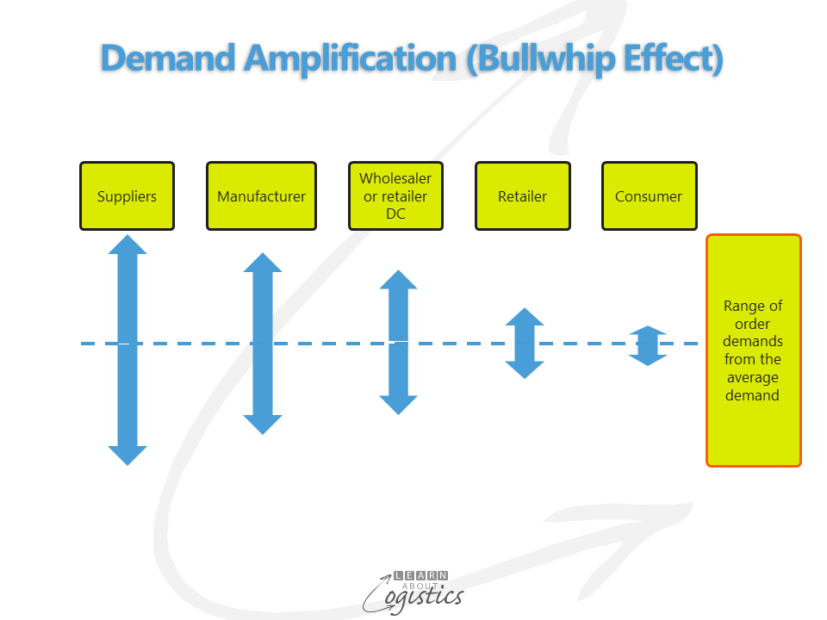

The principals developed by Forrester were enhanced in the early 1990’s and re-packaged as the Bullwhip Effect. This term was used to illustrate the importance of Demand Amplification. The study of the supply chains for disposable babies nappies (diapers) at Procter & Gamble (P&G) showed that similar to the action of a whip, a small change in demand at a point in a supply chain can cause a substantial change in upstream demands. To assist the understanding of Demand Amplification and the role of lead times, the ‘Beer Game’ simulation was developed by MIT as an interactive group role play activity.

In the P&G study, the end consumer (babies) provided a steady demand for the product, but parents purchased replenishment inventory at varied times and quantities, depending on factors such as special offers. Retail stores placed orders on the warehouses (owned or wholesalers) that reflected a ‘just in case’ approach; factories manufactured in large intermittent batches for efficiency and suppliers made in larger quantities to cover the uncertainties of orders. The variance in order size could be greater than the variance in sales; yet all the while, babies consumed nappies at a steady rate!

The four main causes of Demand Amplification were found to be:

- Demand forecasts: using internal order and shipment data, with no input of external sales channel or supplier data

- Order batching: to meet efficiency targets, generate orders on a period basis i.e. monthly, using static safety stock rules and ‘push’ orders through the organisation rather than have customers ‘pull’ orders as required

- Price fluctuation: involves ‘deals’, such as volume buys or ‘investment’ buying, where a lower unit price is offered for higher purchase quantities. In retail, the increased gross margin is offset by decreased net margin, due to added operational costs

- Rationing and shortages caused by large buying orders: customer service decreases if some customers must be rationed to satisfy a large order from one customer. Planners may be tempted to increase lead times rather than manage capacity.

Managing lead times

The term ‘supply chain’ used in articles actually refers to a network of supply chains, operating through complex global trade lanes and typically with a dependence on third party providers in manufacturing and distribution. Your organisation’s Supply Network has uncertainty concerning outcomes, due to the totality of variables, constraints and complexities; the longer each supply chain within the network, the more uncertainty.

As demonstrated by Forrester more than fifty years ago, the cumulative uncertainty increases risks for your organisation and its supply network. Longer lead times increase the Bullwhip Effect across multiple tiers in the Network. Meanwhile, forecasting and planning of your core supply chains is focused on optimising the corporate data and planning signals that exist within the organisation.

Visibility through supply chains remains limited, so there is an inability to identify and account for variability, constraints and complexity across the nodes of your supply network. Action to reduce the Bullwhip Effect and improve responsiveness to customer demands must therefore aim at reducing the lead times controlled and influenced by your organisation. Examples of initiatives to investigate are:

- Relations with customers

- Sales patterns e.g. hockey stick (the bulk of sales are at the end of month) and overstocking at month/year end to meet targets

- Order entry application – identify demands for items that are out of stock

- Pricing and price incentives that influence order quantities

- Payment terms used by customers as order triggers

- Products

- Design products for commonality of parts or ingredients

- Lot and batch size reduction i.e. use ‘quick changeover’ finishing and packing equipment for response to customer demands

- Delay differentiation of SKUs (postponement)

- Planning operations

- Processes for new and revised product introduction e.g. co-ordination of production, distribution and promotion in CPG and FMCG organisations and sales forecast bias for new line items

- Delays from order management system to distribution requirements planning (DRP)

- Fixed costs and ‘economies of scale’ cost structures that encourage large orders

- Link factory planning directly to demand signals e.g. if supplying to retail, try to use retailers point of sale (POS) data

- Inventory control policies i.e. vendor managed inventory (VMI)

- Item (product line) rationalisation – reduce the cost of complexity caused by increases in line items

- Suppliers

- Relationships with non-key suppliers and customers that can affect overall operations

- People

- Align management incentives to Logistics performance objectives such as ‘delivery in full, on time, with accuracy’ (DIFOTA)

Jay Forrester’s initial work was done before supply chains were written about and discussed, yet he identified an organisation’s customers and suppliers as a system that is dynamic and influenced by policies and rules installed by management. He can therefore be considered as a ‘father’ of supply chain thinking.