Country logistics performance

When evaluating the performance of Logistics Service Providers (LSP) across countries in your supply chains, there must also be an evaluation of the logistics capability for each identified country.

Why is this? Because a higher level of performance from logistics services depends on the public sector’s policies and actions, including: attitude to globalisation, regulations, infrastructure, controls and dialogue with industry.

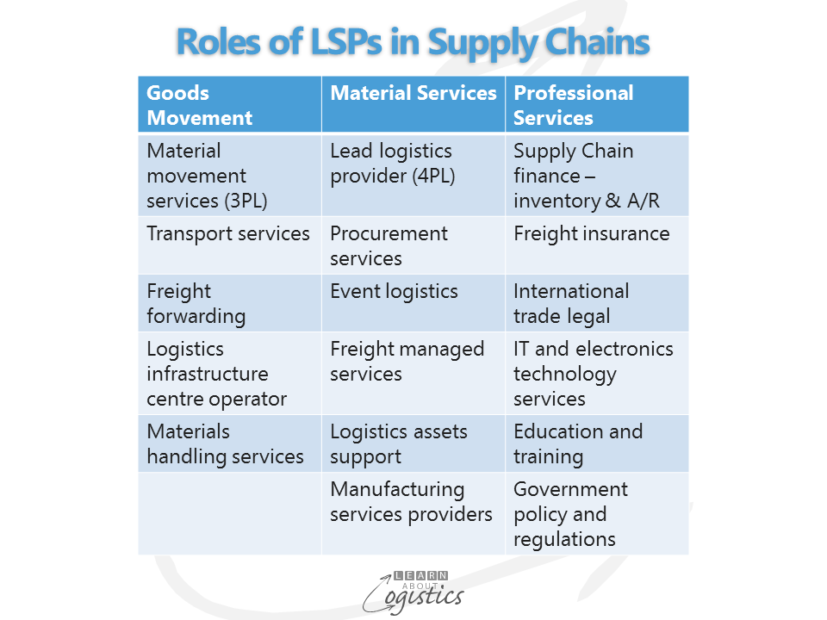

The range of LSP activities that assist shipper organisations in the effective and efficient movement and storage of goods, are shown in the diagram. LSP activities were discussed in the blog Logistics Services Providers scope in a Supply Network

To assist supply chain professionals when evaluating the logistics performance of a country, two influential Indexes are published annually:

World Bank Logistics Performance Index (LPI) 2018. It is an interactive bench-marking tool provided since 2007 and based on a survey of freight forwarders and express carriers, located in each of 160 countries.

DHL Global Connectedness Index (GCI) 2018 The State of Globalisation in a Fragile World by Steven A. Altman at New York University (NYU) Stern School of Business. This fifth edition ranks 169 countries based on their integration into the world economy.

Measurement Indicators

Logistics Performance Index (LPI)

The LPI provides an analysis of a country’s logistics services performance in two categories, with six indicators:

- Areas for policy regulation, indicating the main inputs to supply chains:

- The efficiency of customs and border management clearance

- The quality of trade and transport related infrastructure

- The ease of arranging competitively priced international shipments

- Supply chain performance outcomes, corresponding to LPI indicators of time, cost, and reliability:

- The competence and quality of logistics services

- The ability to track and trace consignments

- The frequency with which shipments reach consignees within the scheduled or expected delivery time

Global Connectedness Index (GCI)

Opinions expressed indicate that a majority of people (at least in developed countries) believe the world is more globalised than the actual situation. In the GCI report, the level of globalisation is measured based on the flows of trade, capital, information and people. Distance and differences between countries continue to serve as constraints on international flows, with the actual situation being:

- Only a net 20 percent of economic output around the world is exported, (adjusting for exports that cross national borders more than once through multi-country supply chains)

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows are about 7 percent of global gross fixed capital formation

- Only about 7 percent of phone call minutes (including calls over the internet) are international and

- About 3 percent of people live outside the countries where they were born

Country performance

In the LPI report, countries included in the top 15 have not changed since the Index commenced. Within the 30 top-performing countries, 24 are members of the (developed countries) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); a proportion that has also not changed. In the Asia Pacific region, only China has moved up a group since 2010.

The GCI report tracks the depth of countries’ international flows relative to their domestic activity and the breadth of those flows across origin and destination countries:

- Depth leaders: tend to be wealthy and relatively small countries. Depth measures help to identify which countries are most exposed to threats from particular types of flows

- Breadth leaders: tend to be wealthy, but are much larger than the depth leaders. Breadth data helps to determine whether that exposure is global or more focused

The GCI report also notes: “In addition to size and levels of economic development, countries’ connectedness scores are influenced by their proximity to foreign markets, whether they share a language with other countries and whether they have direct access to the sea”

So, based on these reports, it could be inferred that to be a top performing logistics services country requires it to be high income. Indeed, high-income countries have a much higher LPI and GCI ranking than low-income countries. However, income is not the sole criteria for performance.

Based on the LPI, the upper middle income range countries of China and Thailand and the lower middle income range countries of Vietnam, India and Indonesia have outperformed their global income group peers. Conversely, resource rich countries have generally under-performed their income group peers. This indicates that only considering income is insufficient in explaining why performance can vary among countries within income groups.

Implementing reforms and policies

In its 2018 LPI report, the World Bank observed that “…countries which introduce far-reaching changes appear to be those that treat logistics (services) as integral to the economy. They tend to combine policy perspectives, such as regulatory reform, trade facilitation and trade and investment planning with seamless inter-agency coordination and strong public–private dialogue”.

As always (and since the 2007 LPI report), the critical aspect to improve a country’s logistics services performance is effective implementation of realistic public policies. The GCI reports states “International flows and their constraints are both formidable and vary over time, across locations and between industries. The biggest winners are likely to be countries and companies that embrace globalisation’s complexity…”

However, there are three factors that are making implementation of public policy more difficult to achieve:

- The scope of implementation has widened. In the past, the focus was on transport infrastructure and trade facilitation, such as removing cross-border bottlenecks. The scope has now widened to include;

- The environmental, social and economic sustainability of supply chains and the resilience of supply chains to disruption or disaster (physical or digital)

- Skills development policies and resources (physical and human) to address workforce and training requirements

- Regulatory and legal framework (domestic and international)

- Planning schemes that take account of commercial transport

- Spatial planning methods and approaches – used by the public and private sector to influence the distribution of people and activities in spaces of various scales – Wikipedia

- Spatial planning includes population and settlement policy and the planning of transport activities

- Transport activities include consideration of urban encroachment on freight infrastructure

- Effective freight infrastructure assets require the flexibility to operate seven days per week, 24 hours per day (24/7)

- Planning overlays need to protect freight and logistics services’ land including freight precincts, ports, rail lines and airports from demands by other potential (and incompatible) users. Negative actions are:

- Curfews and restrictions placed on freight operators in the hope of improving other’s amenity, such as in new residential developments and

- Central Business District (CBD) and inner-urban freight delivery restrictions that reduce the productivity of distribution operations The scope of planning activities required to address the needs of stakeholders

- Spatial planning methods and approaches – used by the public and private sector to influence the distribution of people and activities in spaces of various scales – Wikipedia

- Reforms and policies that concern logistics services involve more than one tier of government and multiple departments or agencies within a government. The many stakeholders can slow or even reverse implementation, if a cooperative framework has not been established

Major improvements to assist the performance of logistics services in many countries is likely to be slow. This is indicated by the evidence of the annual LPI and GCI reports concerning limitations on the ability of countries to change. So, when reviewing your supply chains, is is advised to assume the status quo situation concerning a country’s future logistics services performance.