Planning is critical.

For the flows of materials and money into, through and out of your business to be effective, they must be planned. Planning is a core capability of a successful business; without it, staff become reactive to events. This looks good as a ‘can do’ attitude, running around to ‘put out fires’, but it is an ineffective and expensive way to operate.

Previous posts Use external inputs to your Business Plan with care; Your Business Model will influence the Business Plan and Logistics strategy needs a defined process to succeed have carried a central theme of the ‘one plan’ approach, identifying how each of the planning steps are linked and must be integrated into the supply chains of an enterprise.

On my recent trip to the north west of Australia (the Kimberley), I experienced the situation where, although my group of tourists were of similar age and fitness, when we arrived at an area to be walked, the group quickly became a line with gaps and tour leaders trying to keep the group together. This scenario was described in The Goal, a novel written by Goldratt and Cox over 30 years ago to identify whether (and how) a production line can be planned to minimises work in progress (WIP). Like my experience, the book described a troop of scouts on a hike (later a column of solders on a march was used). In the analogy, the length of the line is equivalent to the WIP, so the challenge is to keep the line short.

Use constraint management in your planning

The theory of constraints (TOC), also known as constraint management, states that operations (such as a complete supply chain, a distribution sequence or a production line) are governed by a constraint in the system. At clients, I have identified constraints to be in order entry, the planning office and materials issuing in addition to the more typical production areas. In a business, it is assumed that people work to be efficient in their area of work. However, the sum of all the performances within individual work centres is not equal to the maximum output for the system or process. This is because the total throughput of the system is controlled by the capacity constrained resource (CCR) – the step(s) in the process that has the lowest throughput.

So, for planning purposes identify the constraint (CCR). Then develop schedules for the total operation that are based on the CCR capacity.This will reduce variability and assist in making an operation more effective.

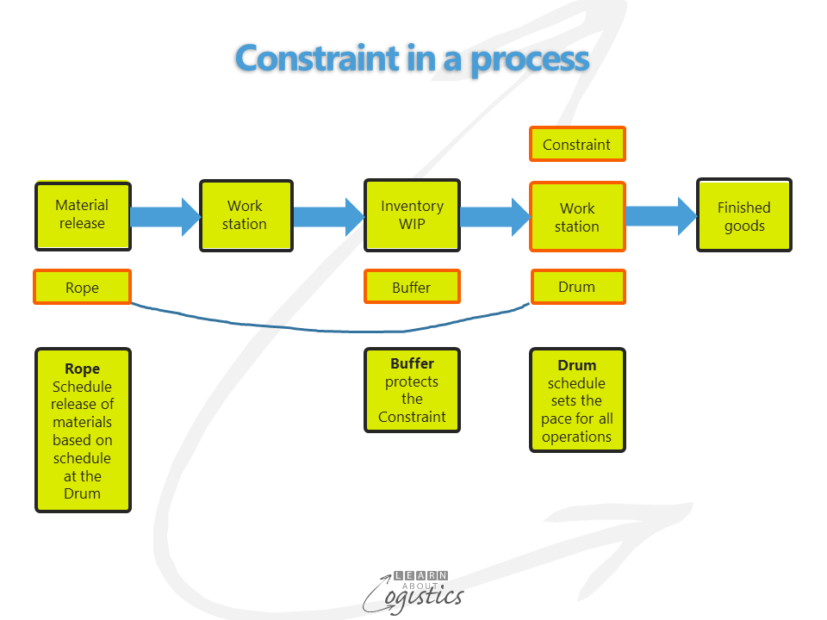

The diagram illustrates a production line, where the constraint is a production work station with the lowest output. This is the capacity constrained resource (CCR) or the Drum that dictates the throughput for the total process. In planning, the CCR must be utilised to its maximum.

The release of materials or orders to all parts of the operation (the Rope) should be at the same rate as the Drum is scheduled, because that is all the system can accommodate. To ensure that the Drum is protected and does not lose any time (which cannot be recovered because the CCR is fully utilised), a buffer of inventory or time is kept behind the Drum. Upstream work centres are back-scheduled from the CCR to ensure the Buffer is maintained. This sequence is referred to this as drum-buffer-rope (DBR).

Applying constraint management

While some advanced planning and scheduling (APS) modules of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems may include constraint management; for most organisations the MRP records and internal knowledge must be used to identify the constraint(s) and its maximum throughput.

The required output, based on market requirements can be evaluated against the CCR and if there is sufficient capacity, the MRP suggested work orders can be accepted, because it is known there is sufficient capacity at all other steps through the process. This approach is a ‘workaround’ due to the design limitations of planning applications in most ERP systems:

- One is the inability to plan material and capacity requirements concurrently. Only when materials requirements have been planned can the detailed capacity requirements be evaluated

- A second presumes there is infinite capacity available at all work centres; therefore, if the materials plan indicates that excess capacity is required, the plan must cycle back for the MRP to re-plan materials. But there is typically insufficient time and people for this to occur.

When planning operations, the CCR should not stop, because an hour lost at a CCR is an hour lost for the total system – whatever the CCR produces will be the same for the total operation. Therefore, staff (permanent part time?) must be available to keep the CCR working through any breaks, such as meal times. Conversely, an hour saved at a non-CCR is meaningless – so much for the focus on department efficiency!

To help ensure the plan is achieved (that is being effective) and to enable maximum flexibility, the process flow structure should be that the finishing and packing closest to the customer has additional capacity. This allows the output of multiple SKUs and time for product changeovers. The outcome that selected equipment will be idle at planned occasions (that is, under-utilised), which can be difficult for accountants to accept. This approach allowed a client to change from a ‘make to stock’ business to ‘make to order’ with a substantial reduction in inventory that funded expansion.

Having identified the CCR for scheduling purposes, an improvement program can be undertaken to identify how the CCR could be modified to remove the constraint; this is continuous improvement of the most costly part of the process. If the constraint is removed, another part of the system will then become the constraint and the improvement process is repeated.