Internal flexibility and responsiveness.

Promotion of eCommerce has increased the expectations of shorter lead times and quicker deliveries of products. This could influence perceptions about lead times within many supply chains, irrespective of their reliance on eCommerce channels of distribution.

The most recent posts have identified that improvements to your supply chains will occur mainly within the core supply chains – and be the responsibility of the Supply Chains group, comprising Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics (inbound, internal and outbound). The reason for not emphasising improvement of the extended supply chains (sometimes called ‘end to end’ supply chains) is because customers and suppliers are reluctant, for commercial and competitive reasons, to share critical data and information.

This view was supported in a conference video that I recently viewed, where panellist from two global beverage corporations stated they were able to sign-up only 30 percent of suppliers to joint ‘sustainability improvement’ programs. If global corporations have such a challenge when interacting with suppliers, then businesses with less power in commercial negotiations are more likely to have a lower level of success.

In addition, Uncertainty (consisting of Complexity, Variability and Constraints) in your organisation and within and between each enterprise of your Supply Network are activated due to circumstances within their Supply Networks. Uncertainty leads to emergent (i.e. unknown) and cumulative results, which are impossible for your organisation to manage. The best that your organisation’s Supply Chain group can achieve is to obtain a good understanding of the Supply Network, which can assist with a quick response to events.

Instability in a business will result if ‘responsiveness’ is promoted. It gets worse if the urgency is transferred to Tier 1 suppliers via variable orders on ‘rushed’ delivery times (and on through the Supply Network), when usually there is limited capability concerning adaptability and responsiveness. Also, organisations will have different capabilities concerning improvements. This can depend on the level of capital intensity and the industry sector to which they belong: primary (hard/soft commodities), producer, converter, fabricator, assembler or manufacturer.

For most organisations, the ability to provide Availability relies on the management of inventory – the buffer between demand and supply. For inventory planning and control the underlying rule is to ‘plan for capacity and execute against demand’, meaning:

- ‘Plan for capacity’ requires an understanding of the capacity requirements for base demand and flexible capacity available to address volatile peaks in demand

- ‘Execute against demand’ requires continual reductions in time (which increases capacity), including:

- reductions in operational set-up times and batch quantities

- reduction in lead times controlled by your organisation – the receipt of items from suppliers, moving items through operations and deliveries to customers

This approach incorporates two elements of inventory; establishing the:

- Order Decoupling Point: the interface between ‘demand pull’ and ‘product push’ in product and materials flows

- Inventory positioning within the organisation’s core supply chains

Order Decoupling Point

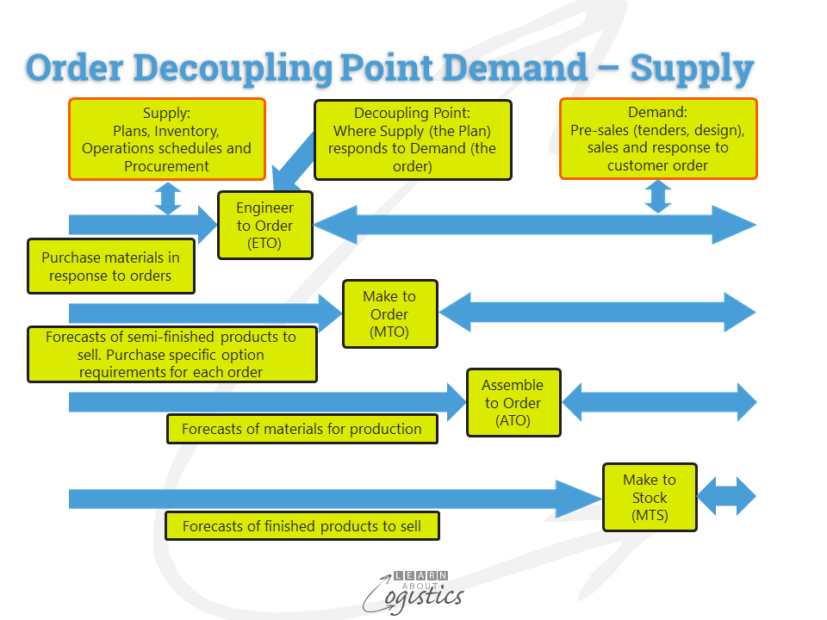

This concept was first discussed in 1984 by Graham Sharman, but he used the term Order Penetration Point (OPP). As shown in the diagram, the Order Decoupling Point (ODP) is where an organisation responds to customer orders. They are accepted and reserved; final product specifications are defined and it is the last point at which inventory to support sales is held.

Sharman noted that the type of operation depends on demand pressures and product complexity. Changing perceptions about speed of response means that enterprises should review their Order Decoupling Point. However, the potential for change may be limited by product or equipment complexity.

The objective of the ODP is to provide downstream flexibility to meet market demands, but also to provide stability upstream for an effective Supply Network. At the extremes, Engineer to Order (ETO) responds only to specific demands from customers and Make to Stock (MTS) produces finished goods based on forecasts. However, both Make to Oder (MTO) and Assemble to Order (ATO) are ‘postponement’ approaches to inventory management, which enable a higher degree of flexibility.

The difference between MTO and ATO products are:

- Make to Order (MTO) is the adaptation of pre-designed products. Provide a design and manufacture service for options to a range of base products. The base item or major sub-assemblies may be forecast and produced in advance of orders, to be held in inventory.

- Assemble to Order (ATO) is to assemble discrete or ‘mix and stir’ process (non-discrete) products to order; based on specific orders from either customers or the sales department for catalogue or recipe products. The business makes or buys based on forecasts for materials, components, sub-assemblies, packaging and options. Holding this inventory enables a business to respond to a customer order through being able to:

- Assemble materials and components or ‘mix and stir’ ingredients into finished goods and deliver, using ‘just in time’/lean flow manufacturing processes

- Assemble and deliver purchased or previously produced and stocked discrete sub-assemblies (MTO)

These are examples of ‘form postponement’ or ‘delayed configuration’, which means that the final configuration of a product is delayed until a firm order is received. The benefits are:

- Value of inventory held is reduced, as inventory is held upstream in an unfinished form

- Forecasting at the generic product level (MTO) or material level (ATO) will have less volatility than at a product SKU level and

- Quick response to changes in demand for finished products, as inventory is held at the component or material level

Planning factors to be considered when moving to an MTO and/or ATO operations model are:

- Flexibility requires excess capacity to be closer to customers for quick response

- In a process business, install multiple (small) holding tanks for low volume batches, processed in short runs on packaging machines purchased for their flexibility (quick changeover time) rather than output speed

- In a discrete business use the principle of ‘one minute exchange of dies’ (OMED) for quick changeovers on machines – it increases flexibility

- Upstream operations from the Order Penetration Point (OPP) are either MTS (for lowest cost) or MTO (for flexibility)

- Speed of order acceptance and acknowledgement

- Planning and scheduling capability (people and IT applications) through to final delivery

- Planning input to forecasts that establish component or ingredient inventory levels

- Holding option components in inventory

As the ‘long tail’ of SKUs increase, businesses with a MTS planning structure could place their low volume items into separate MTO or ATO facilities. This would remove the need for multiple set-ups and short runs on equipment designed for volume based production and distribution.