A strategic (or critical) product or material

The COVID 19 pandemic has highlighted a lack of availability for personal protective equipment (PPE) in healthcare; also, in some countries there has been shortages of imported replacement parts and consumer products, following panic buying.

From a national viewpoint, a strategic sector is critical for a country’s ongoing economy, national security or public safety. Industries and products are subsets of these sectors. Based on the shortages experienced, countries will likely review the sectors, industries and products (domestic and imported) that should be identified as strategic.

Industries for our future

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has identified nine industries likely to dominate future economies:

IT enabled

- Computing hardware

- Nanotechnologies – the control of matter at the atomic and molecular level – nanoscale is about 1 to 100 nanometres. Products that use parts this small are electronic devices, catalysts, sensors

- Quantum technology – applying the principles of quantum mechanics; the physics of sub-atomic particles to provide quantum computing and more reliable navigation and timing systems

- Networking and data communications

- Cryptographic technology – protecting information by transforming it into a secure format

- Machine learning and AI

Equipment

- Autonomous robotics

New Materials

- Materials and manufacturing science

- Synthetic biology – design and construction of new biological entities such as enzymes, genetic circuits and cells or the redesign of existing biological systems

Of more than passing interest to politicians, industry leaders and supply chain professionals, is the amount of crossover between the list above and the policy of China called “Made in China 2025”, published in 2015. This identifies 10 priority industries where China has intentions to control supply chains (with differing intensity), using its capabilities in manufacturing technologies:

IT enabled

- Next generation IT infrastructure (a highly automated platform for the delivery of IT infrastructure services built on top of new and open technologies such as cloud computing to better support business needs of big data, digital customer connection and mobile applications)

- High end computerised machines and robots

- Energy saving and new energy vehicles

- Bio-medicine and high performance medical equipment

Equipment

- Aviation and space equipment

- Maritime engineering equipment and high-tech ships

- Advanced railway transport equipment

- Energy equipment

- Agricultural equipment

New materials

Geopolitical policies and events

Differences between countries have and will develop, as the current (and likely future) state of geopolitics affects global trade. As Forbes magazine noted in August 2018, “Software is driving the world, but the world is still largely a physical machine; the value lies in the inter-meshing of digital and physical”.

China made clear in the Made in China 2025 policy, its intention not to become a services economy, but to remain a major manufacturing economy. The result has been questions raised in countries with services economies concerning their dependence on one country for strategic items, especially those driven by software.

This has implications for development of Digital Supply Chains and Industry 4.0, with its core concept of transnational movement of data and information, in addition to materials and goods. With IT and communications requiring standards, data security and interoperability, there is a likelihood of three information and communication technology regimes: US, EU and China, with other countries maybe required to select their preferred driver.

Assessment of critical industries and products

In a market economy, scarcity of an item usually leads to increased price, with a subsequent reduction in demand. For non-critical items, the higher price of an item provides incentives for businesses and investors to:

- Hold increased ‘just in case’ inventory in different ‘form and function’ at specific locations

- Consider alternative sources for the item

- Consider alternative that achieve the same end user satisfaction objective as the item

- If alternative sources or items are not available in the short term, a business will change their product mix and consumers their buying behaviour

However, items are considered as strategic because scarcity can affect the working of an economy, be detrimental to national security or public safety. To identify whether an item is critical, a valid approach is a risk based assessment. For example, in Germany, the SCARCE method was developed for the assessment of resource materials; but the methodology could be adapted for any item.

The methodology is to initially identify countries that currently supply the item (including raw materials and intermediate goods). Then test for the importing country’s Strategic Dependency, that is: “if a country imports a particular good (or item) and more than 50 percent of its supplies come from any one country and that country controls more than 30 percent of the global market for that particular good (or item)”. Adapted from the report Breaking the China Chain published by the Henry Jackson Society.

However, although a country may have a dependency on a supplier country for an item, the risks associated with that dependency are not necessarily high; therefore the item is not strategic. To rank items for their strategic value requires an assessment of Criticality for an item. This has two risk criteria, with a number of attributes:

- Availability of the item e.g.

- Geopolitical risk for the supplying country and its trade lanes

- Trade barriers that may be erected against the supplying country

- Political stability of the supplying country

- Vulnerability of the item e.g.

- Economic importance of the item

- Long term availability

- Importance of the item in development of future technologies

- Substitution factors i.e. how likely

- Price fluctuations

In addition to the immediate political, economic and supply chain factors in the supply risk assessment, there are country factors concerning longer term supply capability for strategic items:

- Sustainability and Society acceptance criteria of:

- compliance with environmental standards e.g.

- sensitivity of the supply country’s biodiversity to damage

- climate change mitigation and adaptation actions undertaken and planned

- water scarcity

- compliance with social standards e.g.

- human rights abuse

- compliance with environmental standards e.g.

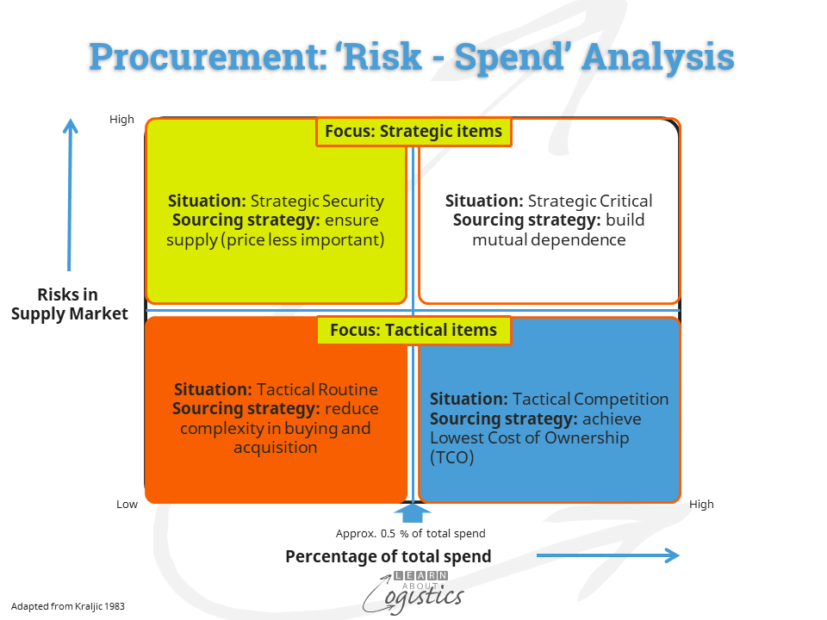

From this assessment, which is similar to a Procurement Spend-Risk Analysis process, items will be placed in their quadrant, depending on the total imports by organisations in the country and the cumulative risk factors.

To ensure supply (Strategic Security) and identified mutual dependence (Strategic Critical), national strategies for sectors, industries and items must be structured. For example, items that are Strategic Security could include strategies of:

- hold national inventory in the country;

- make a defined percentage in the country;

- have the capability to scale-up production in an emergency and

- have the ability to re-purpose facilities for making an item.

Enabling these strategies to address possible shortages of critical items, particularly for the more complex, requires a country to have a breadth of capability in its manufacturing sector. This must be underpinned with an innovation mindset to enable change, combined with production engineering and agile supply chain planning and execution experience, knowledge and training.