Towards Omni-channel.

The underlying processes and techniques of ordering from suppliers, moving and storing items and delivering orders to customers are well established. It is the progressive implementation and use of technologies which has enabled refinement and improvement through supply chains.

Over the past forty years, the introduction and increasing use of home computers, mobile communications, warehouse automation and improved transport infrastructure has enabled mail-order to morph into eCommerce; initially as multi (separate) channels of distribution and now towards ‘omni-channel’.

Omni-channel provides a consumer with the same experience across all channels of interaction with a supplier (often a retailer). This is both physical and digital from the retailer to consumers (inside-out) and receiving digitally from external sources, including social media (outside-in). The mix of channels enables retailers to design targeted sales approaches to different consumer segments; this requires retailers to better understand how consumers search, compare and buy across each channel.

The organisation structure should reflect the flows of orders through the channels, based on a ‘cost to serve’ model for each type of delivery. This requires an understanding and analysis of the total handling, storage and delivery costs and associated working capital requirements. These will be different by country and region, depending on the retail culture and structure, electronic payment systems, communications technology and transport infrastructure.

For example, multiple island economies, such as Indonesia and the Philippines have only about 50 percent percent of their population living in urban areas, presenting additional fulfilment and ‘last mile’ delivery challenges. In most countries of Asia, Cash on Delivery (CoD) is an accepted form of payment, which requires higher working capital by suppliers. Government rules concerning payment of import duties, VAT and sales tax can influence where the delivery centre is located – since July 1 this year, on-line sales of items that are delivered to consumers in Australia from international sites have been substantially reduced, because GST (VAT) is now charged on all these goods.

Cost of delivery channels

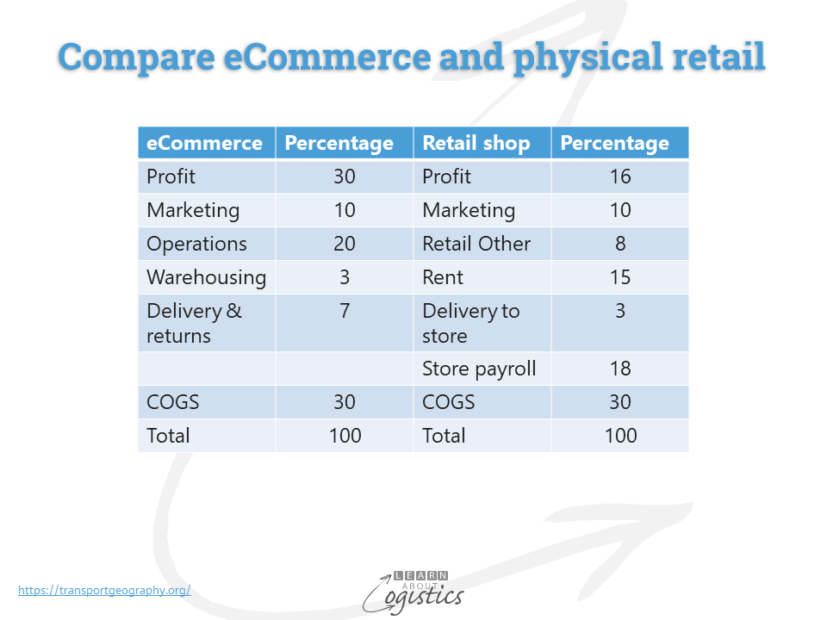

From the view of logistics, a retail shop is a warehouse that stocks individual items instead of pallets and cartons. Orders are picked and paid for by consumers; the majority of whom deliver the items to their final address. This has a low direct labour cost for the retailer. However, on-line shopping requires the retailer to pick the order, load the vehicle and deliver the goods to the consumer – and accept returns. This costs money, whether the tasks are undertaken by the retailer or a third party. The table below provides a comparison of costs for providing apparel in the US.

If both have the same retail price, an online retailer can achieve a 30 percent profit margin compared with 15 percent for a physical retailer. To further improve their market share, online retailers can offer their items at a lower price. However, an online retailer could reduce the price by 10-15 percent while maintaining a similar profit margin to the physical retailer. If costs and margin were the only criteria, all retail would be on-line, but there are additional factors to consider.

Consumers expect the ‘last mile’ of their delivery to be perfect. As the order is an extension of the retailer’s or supplier’s brand, a bad experience could affect future sales. However, in some product categories, retailers have trained customers to expect that ordering items from their desk computer or mobile device and having the goods delivered to their home within a few hours has no value.

As there is ‘not a free lunch’, if the consumer does not pay for picking and delivery (shown as 7 percent in the table), the costs must be defrayed by other means:

- a higher selling price to include delivery and return costs

- provide ‘click and collect’ from a retailer’s store, a locker or convenience store within a range of delivery options

- reduced on-line retailer profit margin

- negotiate lower charges with the third party delivery provider. However, this can lead to a reduction in service levels and customer satisfaction

Under the current scenario, delivery costs will increase. The threats to future profitability of retailers and service providers are likely to be:

- an increased demand by consumers for same-day delivery, because it is provided ‘free’ or below cost;

- increase in the volume of returns, because consumers can order and return at no or low cost

- providing sufficient truck capacity in peak times to meet delivery windows and counter increased traffic congestion. This may require a limit on travel distance for deliveries

- a potential increase of dimensional pricing for delivery. To minimise the effect, identify the order’s actual dimensions and weight and produce packaging to protect the order on-site. This will reduce truck capacity requirements (some commentators consider by 20 percent)

- lack of achieving ‘visibility’ through supply chains; due to the reluctance of software application providers to develop interoperability between applications

Decisions concerning pricing and the range of low or ‘free’ delivery and returns are the responsibility of Marketing, but Logisticians must know the logistics costs of providing inducements to consumers.

Cost of returns

In developed countries, the return of unwanted products purchased on-line are considered by some to be about 30 percent of deliveries. Under the pricing regime of not charging the full cost, returns are likely to increase. To minimise costs, the returns process is an aspect of Reverse Logistics that requires a dedicated and easy to use transport management system (TMS) incorporating:

- recognition of the returned item – return shipping labels with tracking number and barcode

- location where returned item accepted and by whom, or when customer handles the return

- incorporate smartphone cameras and ‘assistants’ to explain why a product is being returned

- selection of transport mode and insurance cover

- tracking of returned items

- inspection process for returned items. If damaged, then decision concerning repair or disposal

- identify patterns of damages as part of a fraud detection application

- re-integration process for an item into the delivery warehouse for resale

To address the challenges of physical and on-line retailing, there is a move for organisations to have both on-line and physical locations. This could eventually result in a physical retail store as the place that integrates the shopping experiences, being located adjacent to similar outlets and ‘destination’ activities e.g. entertainment and services.