Inventory management challenges.

An effective inventory policy is a good theoretical objective, but at a practical level, it becomes difficult to achieve. This is due to senior management’s views concerning the role of inventory and the knowledge and skills of supply chain and logistics professionals to structure a decision making process for an inventory policy.

An example of the challenges has recently been given publicity. ‘Fast fashion’ is a term used to describe a group of retailers that rely on fast turnover of changing apparel designs sold at ‘affordable’ prices to attract consumers into making regular purchases. Inventory management should therefore be a principal business objective; however, this business model failed the Australian licencee of a UK based fast fashion retailer.

Media reports state that decisions concerning range and price were decided in the UK. Clothes were manufactured in Asia, then transported to a a warehouse in Britain, where the items were unpacked and re-priced. The re-packed items were then flown to a DC in Australia for distribution to more than 20 retail outlets, often months later than required. This resulted in poor stock levels, with common sizes not available for months. The expensive logistics processes became a contributor to Australian consumers paying up to 35 per cent more than their UK counterparts for equivalent items.

Amazingly, at the time of calling in the administrators, the business announced its entry into omni-channel distribution, surely without recognising the added complexity! It stated that physical stores would act as distribution centres, offering ‘click and collect’ and free express delivery services. However, this approach would require on-line access to accurate information for customers concerning, at least, SKU locations and fulfilment times – data the company could not rely on.

Other examples of poor inventory management are:

- 24 percent of warehouse space used to hold items that provided four percent of sales;

- an audit team singing ‘happy birthday’ to an inventory stack they counted the previous year;

- building an automated high rise warehouse for finished goods inventory that held three times the total amount actually required;

- excess inventory of imported items; due to not undertaking a total cost evaluation of airfreight replacing sea freight and so reducing inventory levels

Similar examples will continue to be experienced, often because senior management and supply chain executives do not have an agreed understanding of Inventory management. It contains three elements:

- Inventory policy, measured at the cumulative level. This identifies money the enterprise will invest in inventory, based on a rigorous evaluation of the physical options

- Inventory planning; undertaken and measured at the product or family group level

- Inventory control; undertaken and measured at the stock keeping unit (SKU) level

Establish an Inventory policy

Part of the challenge for inventory management is that the process for establishing the inventory policy can be weak. Senior management can often view inventory as a financial item (inventory is an asset in the Balance Sheet), with a financial rather than physical objective. Instead of stating the maximum investment in inventory, the process should identify the total inventory required to support the business model and the consequential commitments that will be made to suppliers in the supply chains.

If Finance cannot financially support the physical inventory, then the business model will need to be reviewed. To achieve this outcome, Finance will need to be convinced of what the Supply Chains group are proposing – not an easy task! The inventory analysis should include:

- Locations where inventory is held (owned and leased premises, customer location, supplier distribution centre, third-party intermediate facility) etc.

- Centralised or decentralised locations; the latter is more likely for an enterprise offering on-line ordering and quick home delivery

- Customers and channels that could be served from each location

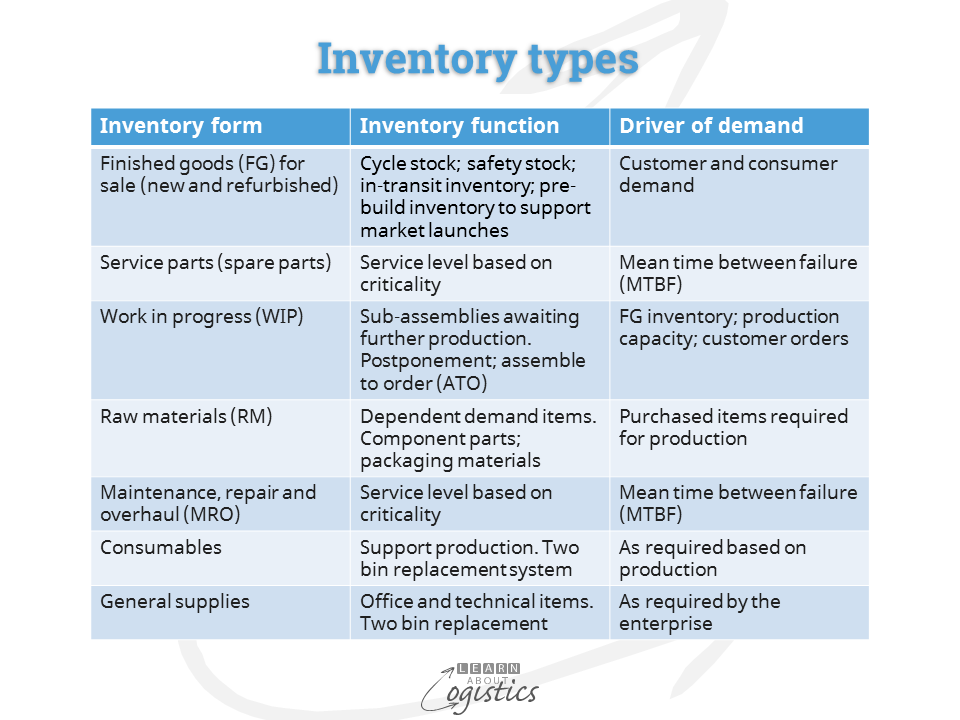

- Form and function of inventory at each location. The understanding and analysis of this could improve an organisation’s inventory turns.

An additional factor to be considered is the actual Lead times from suppliers and to customers, plus calculating the lead time variability. The longer the lead time, more inventory must be held; the higher the variability, the more safety inventory must be held to guard against stock-outs. Not accounting for lead time and variability can result in safety stock levels being too low to meet customer service requirements. This situation can be minimised if ownership of the items is taken at the point of collection for the item. Inventory then becomes a part of the organisation’s ‘moving and tracked’ warehouse assets, but also incurs the costs of moving the items.

Also, identify the gross margin by product group and contribution; this provides input to the relationship between revenue, lost sales and the required inventory investment.

The more options available concerning supply and distribution, the more complex becomes your supply chains. Risk in supply chains equals the level of Uncertainty, which comprises the totality of Complexity, Variability and Constraints. A complex supply network of many international and domestic suppliers, together with multiple channels of distribution for finished goods, results in inventory policy decisions being complex in their analysis.

Inventory policy decisions could be made sequentially – select the inventory locations, assign customers to be served from each location, then identify the inventory strategies at each location. However, this approach does not allow the range of alternative location combination options and their costs to be considered. Spreadsheets are not sufficient for the task. Instead, multi-factor analysis is required to address the complexity of so many options; however, only small specialist software firms and consultancies are developing solutions and few organisations have the in-house supply chains analysis expertise.

For most organisations, they currently have a less than optimum decision criteria for establishing an inventory policy. While less than ideal, it is another area where supply chain professionals need to understand the potential and when ready, gain the expertise and sell it to senior management and Finance.