What decisions are made.

Senior people in government and business can make edicts and statements about financial matters without any factual basis. It is others that have to work within the meaningless constraints or recover from the unintended consequences.

This week, the head of Australian Treasury made a statement that expenditure by the federal government should not exceed 25 percent of the country’s GDP. No justification was given, no basis of research as to why 25 percent was a good target to maintain the country’s AAA credit rating. A quick Internet search shows there is no correlation between low government expenditure and a AAA credit rating. Yet the statement will be the basis for government policies.

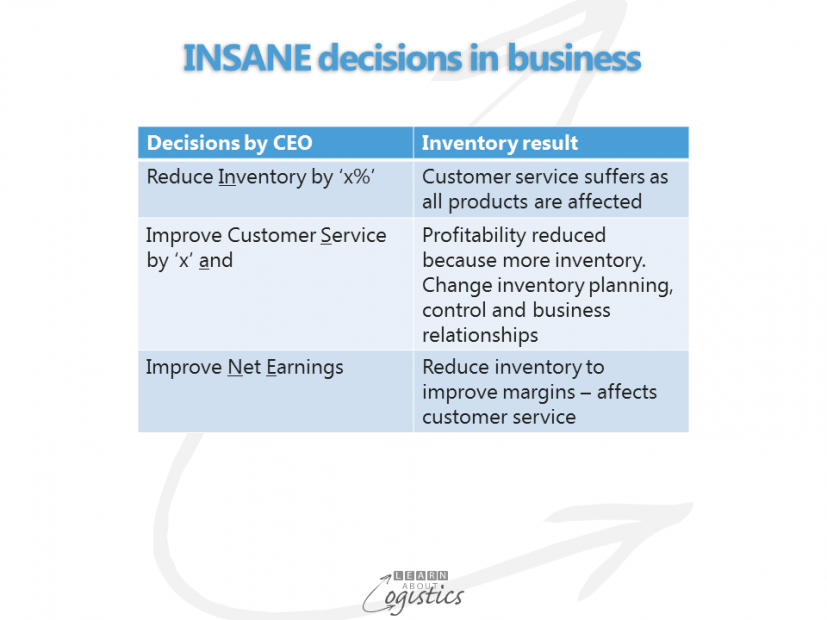

Likewise CEOs make edicts about cutting costs – usually a nice round number like 10 percent; again with no justification or evidence. Inventory ‘guru’ Hal Mather referred in his presentations to ‘the INSANE approach to inventory’. By this he meant the approach to business decisions by CEOs which have unplanned consequences for customer service and the supporting inventory.

You may have experienced the INSANE sequence. Senior management can make other decisions that also have a detrimental effect on the management of inventory (and the business):

Phantom sales targets, whether annual, quarter or monthly. The sales director (or similar) convinces all that substantial increases in sales are possible. The new target requires a pre-build of inventory at additional cost and effort. When the inflated sales do not happen, all other functions are blamed for the targets being missed. From a customer service viewpoint, the first day of a new month is no different from the 30th day of the previous month; their immediate requirement is delivery of the order in full and on time (DIFOT).

Sales promotions implemented to justify a sales target, rather than build a brand. Price promotions require an inventory build and additional delivery costs – costs that are not charged to the promotion, which make the initiative appear more profitable than the actual situation. National promotions, due to their size, are known, but promotions for a product line in a state or province can happen without a trigger to increase inventory. That is until the state sales manager contacts the DC to ask what has happened to the the additional inventory. Or try delivering on a ‘buy 12 get one free’ offer when the standard distribution multiple is 12!

Advertising decisions can provide a created seasonality. If advertising is shown prior to a peak in consumer demand, such as Christmas and Chinese New Year, then the peak grows higher. If the item is imported or has imported components, it requires ordering earlier for more items and overcoming shipping capacity challenges. A sort of seasonality can also occur with erratic advertising. Promote an offer or product, then stop. Consumer demand (and inventory) increases when advertising occurs, but demand decreases when a competitor promotes their offer.

Payment term and payment time discount decisions also affect inventory. If orders are paid against statements that are sent on pre-defined dates, then customers bunch orders to take advantage of the payment terms. This requires increased inventory to satisfy the orders.

What to do about these decisions?

Each of the above decisions are typically made within a silo function, with minimal reference to other silos in the organisation. Even though observers and commentators of Supply Chains have been promoting (and on a few occasions implementing) Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP), it remains a strategic planning tool used by few organisations.

Within a correctly implemented S&OP environment, inventory has a critical role. It is not just an asset or a cost, but a facilitator to building the business. Inventory is an integral part of the organisation’s Supply Network design; not just the location (node) in the network (own, customer, supplier, LSP) but the form (components, intermediate, finished) and function (cycle, safety, in-transit, promotion build) of inventory to be held at each node.

Within the Supply Network design will reside management decisions that are often not formally discussed; but also have a direct affect on the amount of inventory in the network. Examples of these decisions are:

- The number of product lines and SKUs sold by the business. Adding new product lines or line extensions is expected, but getting slow and obsolete (SLOB) lines removed from the product list is much harder. The more SKUs, the more cycle inventory.

- Global inbound Supply Chains may appear to have lower costs, but how many organisations know their total cost of ownership (TCO)? The more nodes in the network, the more inventory; the more transport links in the network, the more in-transit inventory; longer lead times requires more inventory.

- Internal Supply Chains (including outsourced operations activities) require reliability in the processes; the more variability then more safety inventory is required

- Outbound Supply Chains that exhibit demand volatility (that may be enhanced by price promotion activity) require more inventory

For Logisticians, the major influences on the effectiveness of their Supply Chains are: uncertainty, complexity, variability and constraints. The more of each in the business, the more inventory must be held to ensure customer satisfaction. But rather than making edicts, such as ‘reduce inventory by 10 percent’, a thinking CEO and CFO will demand analysis of the Supply Chains. Inventory levels can then be calculated, rather than guessed, enabling achievement of your organisation’s aim and objectives.