Geopolitical factors

The uncertainties generated by ongoing trade tensions between the US and China and other inter-government trade disputes have initiated reviews by enterprises of the international supply chain operations they own or have outsourced.

In addition to the cost implications of changes to supply chains, there are other factors affecting logistics to consider (where to relocate distribution and maybe production to meet changing demands) for each country under consideration.

A recent Blogpost discussed interactions in Geopolitics and within and between the constituent factors:

- Geography

- Culture

- Demography – the statistical study of the size, structure and distribution of populations

- Politics – the way that a country is governed and how a government makes rules and laws

- the Economy (including investment in logistics infrastructure)

- Technology acceptance and implementation

- Military and security

- The influence of surrounding countries and communities, based on their geography, power and constraints

While the geography of a country governs consideration of physical enablers and limitations for logistics activities, a study of the people factors including culture and demography, provides an insight into work and community aspects. Understanding these is necessary, with reference to the acceptance by a country of outside organisations, employment of foreigners and expectations of their behaviour.

The book Rule Makers, Rule Breakers – How Tight and Loose Cultures Wire Our World by cultural psychologist Michele Gelfand, provides an understanding of how culture is the fundamental driver of differences between populations.

Tight and Loose cultures

The author questions why relations between and within countries are divided, despite the fact that people, organisations and governments are more technologically connected? She argues that national and group behaviour depends a lot on whether the culture is ‘tight’ or ‘loose’.

Tight cultures: Throughout history, some cultures have experienced or face a high degree of threat, such as:

- Disasters, diseases or food scarcity

- Chaos of invasions or internal conflict

These cultures have favoured strong society norms and autocratic style leaders, because strong norms are seen as needed to help groups survive. There is little tolerance for deviance – citizens are expected to’ obey the rules’ concerning co-existence and fines or worse are levied for deviations. There can be an emphasis on respect for those in authority, cleanliness and punctuality.

However, tight groups are less innovative, more ethnocentric and more resistant to new ideas. And, as people age they become more conservative and desire order, therefore a tendency towards tightness.

Loose cultures are the opposite of ‘tight’, because there are fewer threats. As there is less need for co-ordination against threats, strong norms do not materialise. Therefore, there can be casual norm violations such as arriving late for business meetings, littering, jaywalking and arguing loudly on the street.

However, having safety enables the culture to explore new ideas, accept newcomers and tolerate a wide range of behaviours. Loose groups are more disorganised and experience self-regulation failures, yet excel at openness – they are more tolerant, creative and flexible.

Understanding the differences between Tight and Loose cultures can help to explain patterns of tension and conflict. As threats arrive, groups tighten; as they subside, groups loosen. However, threats do not have to be real – if people perceive a threat; the perception can be as strong as reality.

Threats can lead to a desire for stronger rules and obedience to leaders who promise to deliver a tight social order. The perception of a threat can lead to an evolution of tightness – a factor which can be exploited by right and left wing autocratic posturing politicians.

Culture and a business management model

Enabling supply chains to change without undue disruption in the current operations of an enterprise requires a management model that is adaptable and responsive to change. A management model, or ‘how things are done around here’, identifies how outcomes will be achieved through people (the employees, both management and staff).

Within the management model should be recognition that the positive response of employees to change is fundamental for ongoing success. However, the approaches will differ because cultures differ, not because one culture is ‘better’ than another.

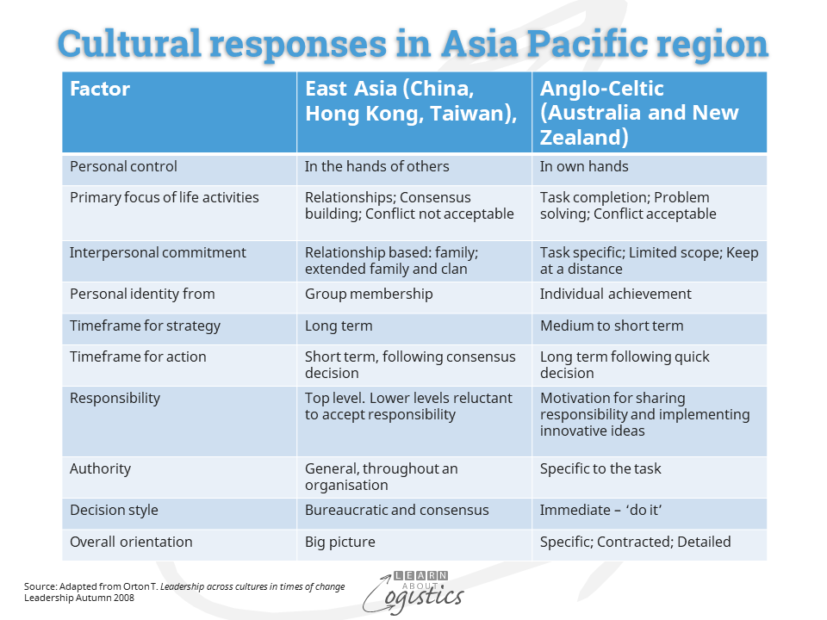

An example of different cultural responses in the Asia–Pacific region is shown in the table below. Organisations need to develop similar tables, which indicate possible cultural responses in supply chain workplaces for each country being considered.

Demographics and supply chains

Overall population trends will impact international trade lanes; projections indicate that by mid-century, India and Southeast Asia will hold the highest percentage of the world’s population (and therefore consumers).

From a demographic view, the potential impact on supply chains is from four factors – infrastructure requirements, population growth, ‘urbanisation’ and ageing. The changes will affect both ends of supply chains, requiring executives to rethink not only where customer demand will be, but also where businesses should locate production and distribution to meet that demand.

- When governments invest in infrastructure, demographic characteristics of the population will influence investment priorities. Should it be for schools or agriculture, or transport infrastructures – to facilitate trade and economic growth?

- Population growth and decline, which can occur within a total population or sectors within it:

- Nations with declining birth rates may see labour shortages in sectors such as distribution

- Countries with a growing middle class can experience changes in people’s career choices, tightening the supply of managers and supervisors in production and distribution activities

- Urbanisation: The available labour pool in the potential country or state (province) will be identified. Migration of people from rural areas to cities can help with the availability of labour. Also the international migration of skilled and qualified people, if allowed by a country’s government

- Ageing of a population: An ageing population will bring changes in the participation rate for work. While older workers can be more reliable, they may lack the strength and stamina required of traditional warehouse jobs. Investing in automation can reduce the physical strain on older workers while achieving throughput and productivity targets

Culture and Demographics are not absolute determinants of an economy, but they are a key determinant for an economy’s potential. As the culture and age structure of a country’s workforce changes, so will the kinds of jobs the economy employs and should be recognised in an organisation’s review of a country’s logistics potential.