‘Bullwhip’ effect

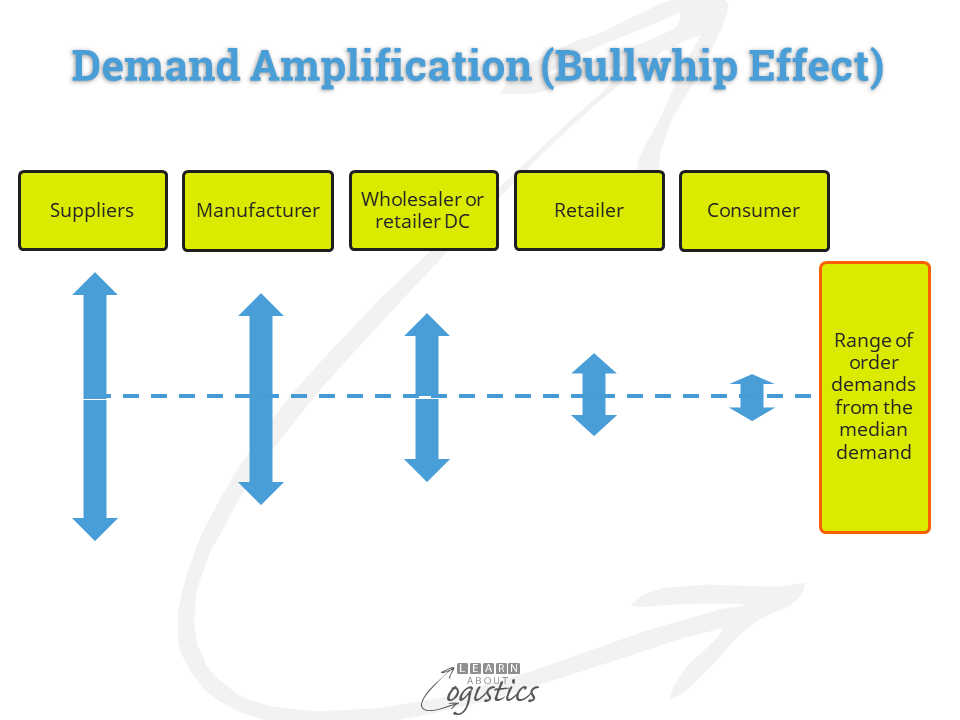

The ‘Bullwhip’ effect is Demand Amplification, where a change in demand at a Node in a supply chain has a more substantial change in demands further upstream in the chain. Orders placed on suppliers tend to have a higher variability than sales made to buyers.

Retail stores place orders on warehouses (owned or at wholesalers) can reflect ‘just in case’ thinking; supplier factories produce in large but intermittent batches for efficiency and lower tier suppliers make in large quantities to cover uncertainty about the timing of orders. In FMCG (fast moving consumer goods) and CPG) (consumer packaged goods with a use-by date) sectors, potential changes in the pattern of consumer demand makes inventory planning increasingly difficult for suppliers across the Tiers.

This cumulative uncertainty increases supply risks for your organisation and its Supply Chains Network, which has its own dynamics by which Nodes react to actions of other Nodes in the system. Meanwhile, forecasting and planning an organisation’s core supply chains is typically internally focused on optimising the corporate data and planning signals.

This phenomena was identified in the 1960s by Jay Forrester (the Forrester effect) and promoted as the ‘Bullwhip’ effect by Hau Lee in the 1990s. And while many have played the ‘Beer Game’ and recognised that the outcome is not good for effective supply chains, identifying the situation is still not part of software applications. So, we must rely on Excel.

Measure Demand Amplification

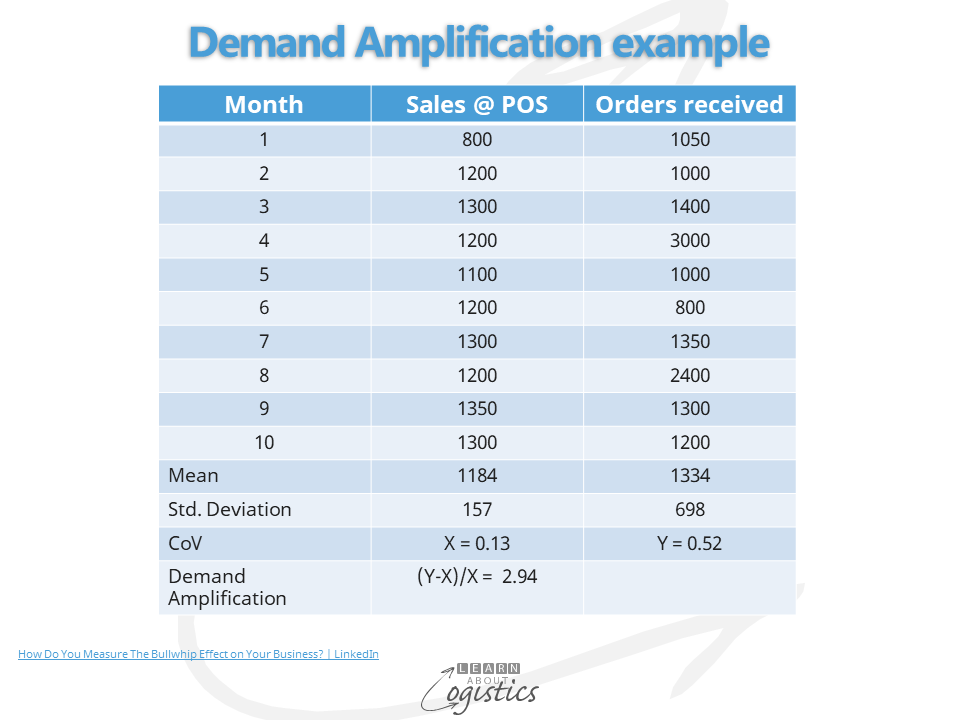

A newsletter written by Fred Baumann explains how using the Coefficient of Variance (CoV) enables the Demand Amplification to be calculated for an SKU. The table used for the example is:

The calculation of CoV for a set of values is the Standard Deviation divided by the Mean. The Demand Amplification Factor (or Bullwhip) is calculated as the difference between the CoV of orders and sales divided by the CoV of sales. In the example, the factor is nearly 300 percent, a not uncommon figure and which is likely to gain the attention of senior management.

Reduce the Demand Amplification

The Demand Amplification obtained from all SKUs by customer enables a grouping of the highest and to work on a plan of action. Although it was thirty years ago, the four main causes of the Demand Amplification (Bullwhip) effect identified by Hau Lee remain current:

- Demand signals: companies use internal order and shipment data, with no input of external data from sales channels

- Order batching: to meet efficiency targets, companies generate orders on a period basis i.e. monthly, using static safety stock rules and ‘push’ orders through the organisation rather than have customers ‘pull’ orders as required

- Price fluctuation: involves ‘deals’, such as volume buys or ‘investment’ buying, where a lower unit price is offered for higher purchase quantities. In retail, the increased gross margin may be offset by decreased net margin, due to additional operational costs

- Rationing and shortages caused by large buying orders: customer service decreases if some customers must be rationed to satisfy a large order from one customer. Planners may be tempted to increase lead times rather than manage capacity

Visibility through supply chains is limited, so there is Uncertainty due an inability to identify and account for Variability, Constraints and Complexity across the Nodes and Links of your organisation’s Supply Chains Network. To reduce the Bullwhip effect and improve responsiveness to customer demands therefore requires a reduction in lead times controlled and influenced by your organisation. Examples of initiatives to investigate are:

- Relations with customers review:

- Sales patterns e.g. hockey stick (many sales at the end of month – ‘end of month rush’),

- Overstocking at month/year end to meet sales targets

- Payment terms used by customers as order triggers

- Pricing and price incentives that influence order quantities

- Fixed costs and ‘economies of scale’ cost structures that encourage large, irregular orders

- Order entry application – enhance the Available to Promise (ATP) application as the customer service tool. Include a function that identifies demands for items that are out of stock

- Cost to Serve for categories of customers

- Sales patterns e.g. hockey stick (many sales at the end of month – ‘end of month rush’),

- Products review:

- Design products for commonality of parts or ingredients

- Delay differentiation of SKUs (postponement)

- Lot and batch size reduction i.e. use ‘quick changeover’ finishing and packing equipment for response to customer demands

- Design products for commonality of parts or ingredients

- Operations Planning review:

- Availability and use of ‘outside-in’ data and information

- Link Operations Planning directly to external demand signals e.g. if supplying to retail, use retailer’s point of sale (POS) data

- Use Scenario Analysis and Planning and Predictive Analysis as Risk Management tools to manage potential disruptions in supply

- Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) as the tactical planning engine of the business

- Item (product line) rationalisation – reduce the cost of complexity caused by the ‘long tail’ of low selling SKUs

- Inventory control policies i.e. promote vendor managed inventory (VMI)

- Availability and use of ‘outside-in’ data and information

Connect Demand Amplification and Supply Chains

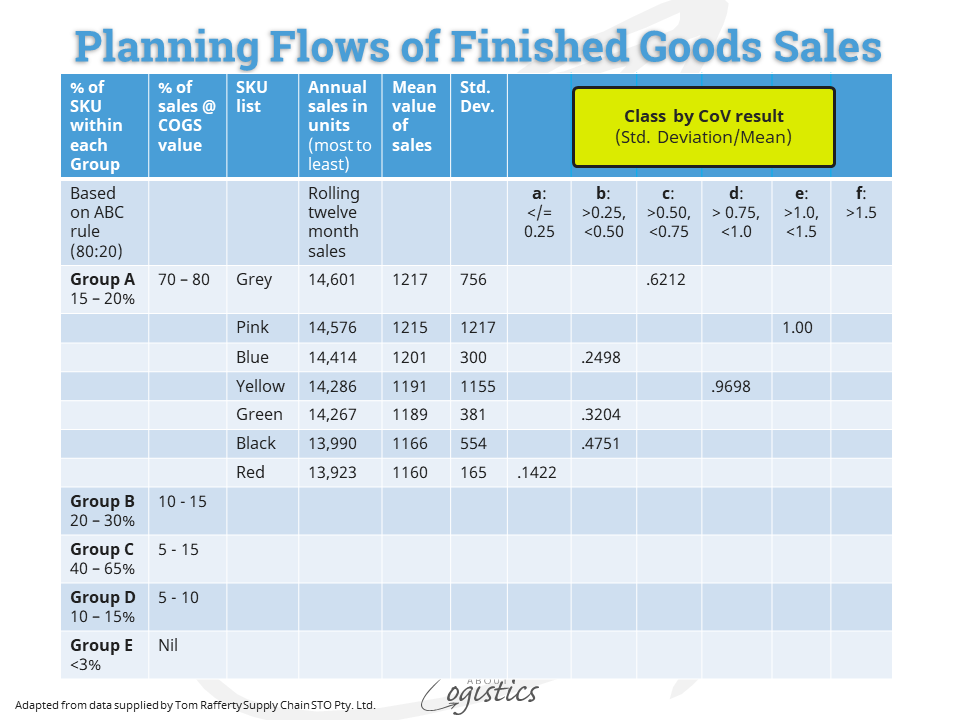

An earlier blogpost discussed the number of supply chains in a business. It noted six factors that influence the structure of an outbound supply chain. The first factor was consolidating SKU sales within patterns, using Coefficient of Variance (CoV) as the tool.

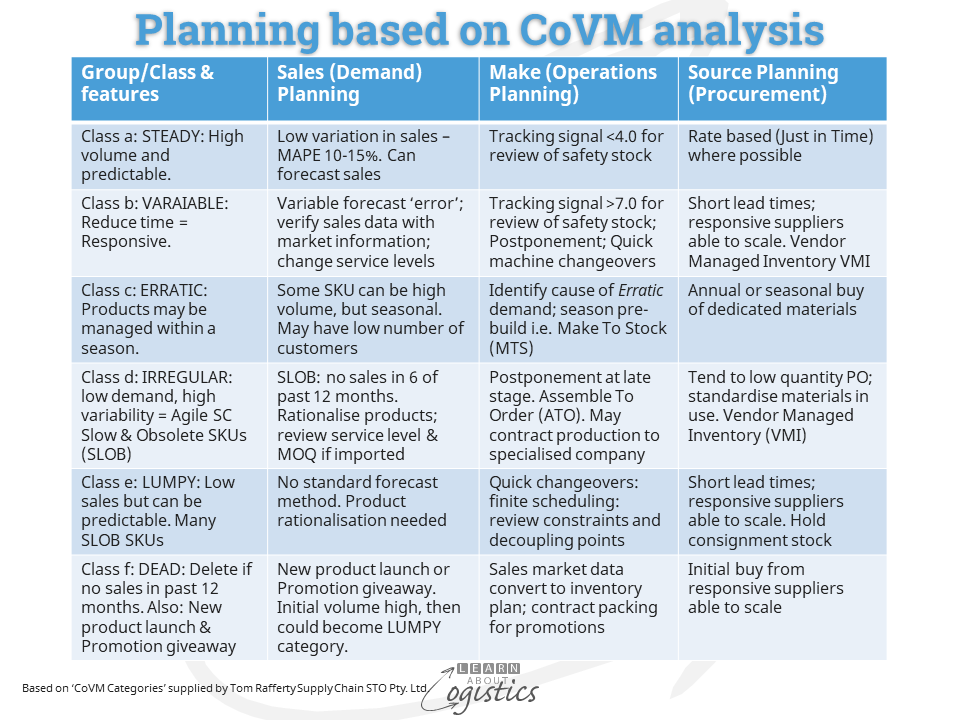

Although each SKU has similar annual sales, placing their CoV by Class identifies the required response by Logistics, Operations Planning and Procurement to effectively serve customers, with each having its own supply, inventory and delivery characteristics and flows – that is a supply chain.

The chart commences on the left side with the breakdown of SKUs by sales using the Pareto principle (or 80:20 rule). The next column identifies the value of each group by its Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) value. The name or code of each SKU follows, using colours in the example. The next column has annual sales, updated each month on a rolling twelve months basis. The Mean value and Standard Deviation of sales is the same as calculated for the Demand Amplification factor. The Class is identified from the CoV calculation.

For each Class, the chart below provides examples of what needs to be considered under the three planning regimes, which indicates the best fit for a supply chain.

Given that the (Bullwhip) Demand Amplification factor and Planning Flows (supply chains) are calculated using CoV, they can be built into the one application – initially a spreadsheet. This provides the basis for planning supply chains from a numerical base, which places the Supply Chains group on firmer ground when internally negotiating for change.