Uncertainty in Supply Chains

Global, but potentially fragile, supply chains have been created over the past forty years. However, the assumptions of an era with relative stability and lower risks has passed, so future developments in supply chains are largely uncertain.

The analysis of Risk in supply chains was discussed in the previous blogpost. This considered a period of up to five years into the future – the typical length of a supply chains strategy. However, increasing uncertainty requires thinking about risks and opportunities in supply chains within a longer period, say between five and ten years. This process is called Scenario Planning, developed in the 1970s as a corporate planning tool.

The concept and methodology was to develop different views of the future, analyse their possible likelihood of occurring and consequences and therefore be better prepared for future developments. This approach can also be used to consider an organisation’s Supply Chains Network.

Scenario Thinking

A role for the Supply Chains group is to translate uncertainty about supply chains into thinking about future scenarios. A challenge is that factors being considered can interact and amplify with each other. And, there will be bias from participants concerning data and information, analysing trends, possible disruptions and describing scenarios.

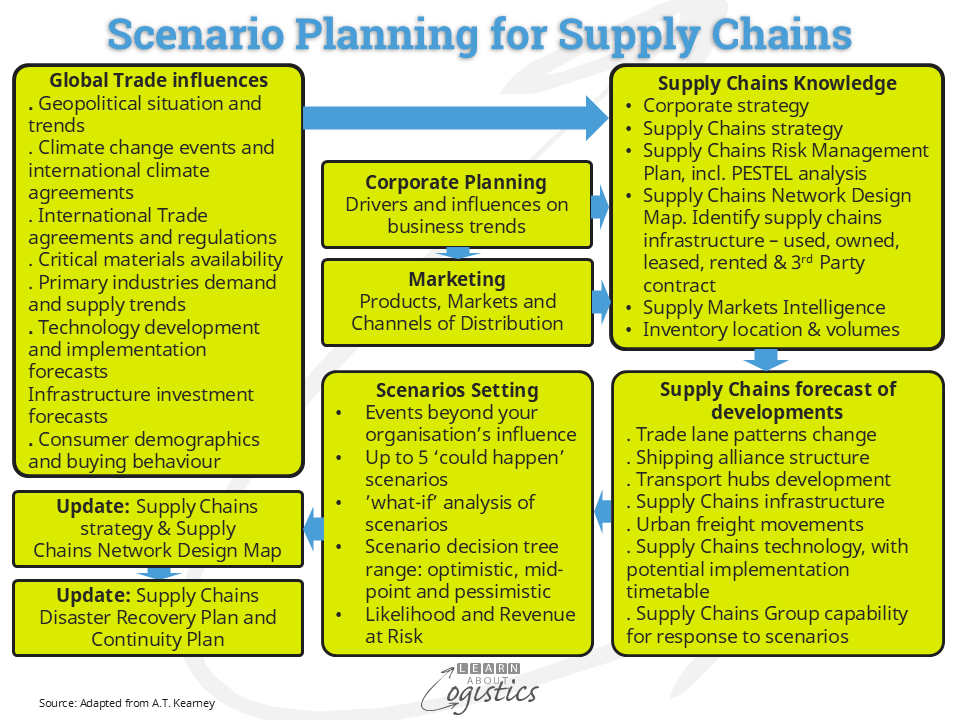

The diagram illustrates the four step process for Scenario Planning (influences, knowledge, forecasts and scenario setting). Sufficient background information must be available from the Supply Chains Network Design Map and the Supply Chains Risk Management Plan.

The Design Map identifies your organisation’s current supply chain vulnerabilities at infrastructure locations. Questions to ask about your organisation’s critical vulnerabilities:

- What is the expected Time to Recover (TTR) if critical inventory Nodes or transport Links become unavailable? What are the alternatives available?

- The inventory form and function required at location Nodes when supplies are limited

- IT and communication potential failures and the risk of cyber security attack through the organisation’s supply chains. Identify the alternatives available

This provides a reasonable assessment of the likelihood and consequences in any situation. Additional analysis should also be done based on Supply Markets Intelligence, concerning factors and forecasts in supply chains that could become potential inter-dependent trends and influences, such as:

- Trade becomes more regional. Trade flows increase between ‘friendly’ countries and blocs. Trade facilitation agreements (called FTAs) that could influence trade lanes and flows in the scenario period

- National governments increase protection for industries and companies that could influence supply, through providing subsidies, concessions, local content rules and direct spending on industrial sectors

- Hub ports are attractive to shipping companies, but the increased size of container ships limits access to ports. Shippers might prefer to send smaller shipments via ‘point to point’ services, which includes smaller ports. Also, Hubs (for ships, aircraft, trains and trucks) could provide a ‘shuttle’ service between the ‘hub’ and final destinations. Goods are then distributed using multiple warehouses and small transport units. The EU has estimated that the added costs are 2 percent of it’s GDP.

- Shipping alliances: At some time in the future, more than 80 percent of sailings could be controlled by a few large shipping or multi-modal transport groups (Gartner). To ensure full ships, there could be limited sailings to only a few selected ports, with higher freight rates. Container capacity availability could be aligned closer with demand to reduce fluctuation in freight rates

- Growth of the land-bridge between China and Europe and the influence on sea container volumes

- Direct transactions between buyer, seller and transport operator could reduce the need for forwarders, consolidators, brokers and Non-Vessel Owning Common Carriers (NVOCC)

- Production technologies could encourage cost-effective local production of some items, which results in reduced demand for inventory, warehouse and transport

- Information technology: direct booking of cargo, automated document flow and ‘track & trace’ capability of orders reduces the need for facilitators through supply chains

- Climate Change: storms and flooding have potential for significant damage to ports and hinterland infrastructure.

- Future pricing of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for your business, demand and use of low-carbon materials

Scenario Planning

Outputs from the ‘thinking’ process provide inputs for four or five supply chain scenarios that could influence your organisation’s future supply chain structure, operations processes and external relationships. The value of Scenario Planning lies in the discussions around options, risks and the likely consequences, so when considering possible scenarios, the Supply Chains group must think broadly. If Scenarios are restricted to those being ‘realistic’, the scope has been limited due to bias of individual’s perceptions and opinions.

Consider the risk category of ‘Unknown-Unknowns’, where scenarios only need to be plausible. These could include: the collapse of a major economy, the overthrow of a government in a large developed country, a significant military conflict, a catastrophic climate event that causes mass migration and famine and a global pandemic. The risk category of ‘Known-Unknown’ refers to disruptions that are likely, but the consequences to the business could be variable, such as a regional conflict where ‘critical materials’ are mined and changing international political relationships. However, within these categories, the perception of countries as customers or suppliers can also change to be a positive for sales or supply.

An additional factor is the potential for events in one or more countries, industries or companies (especially at Tier 2 suppliers and below) to have inter-dependent connections and decisions that can affect supply and demand patterns.

Scenarios can be manipulated with ‘what-if’ options, such as: change inputs and output volumes; expand, contract or postpone operations; terminate a project or operational direction and phase an implementation to conserve resources. Using ‘decision tree’ diagrams, options from optimistic to mid-point to pessimistic at each fork in the tree can be compared, by applying the discounted cash flow (DCF) technique to the ‘Revenue at Risk’.

After evaluating the scenarios, a scoping document is developed, identifying the risks and opportunities within supply chains. Based on criteria of Availability and Vulnerability and Complexity and Relationships, possible alternatives are discussed, such as: suppliers, routing through different transport points, storage locations, inventory policy, supply chain organisation structure and indicative time and costs for implementation.

The biggest challenge is then selling the ‘solution’ to your CEO and senior executives who may not have been a participant in the process. Looking into the future could be considered as a TWA – ‘time wasting exercise’; but that is not so. For supply chain professionals, they obtain a clearer understanding of likely scenarios and therefore have more flexibility to prepare and adapt Operations as events happen.