Uncertainty in supply chains a reality

The three broad inputs to Uncertainty are Complexity and Variability, discussed in previous blogposts and Constraints. As an input to Uncertainty, Constraints have been a minor factor, but increasing geopolitical tensions and threats from climate change will make Constraints more visible.

A Constraint (also called a bottleneck) is defined as ‘something that controls what you can do by keeping you within particular limits’, so a Constraint contains an element of permanency. The practice of Constraint Management incorporates the Theory of Constraints (ToC), developed by Eliyahu Goldratt in the late 1970s. ToC recognises that the current output from an operation, such as from Nodes through a supply chain, a distribution procedure or a production line, is governed by a constraint in the process – the step that currently has the lowest throughput. This is called the capacity constrained resource (CCR).

Identify the CCR

Although some planning and scheduling applications may include constraint management, for most organisations the ERP system records and internal knowledge are used to identify Constraint(s) and their throughput.

Within an organisation’s facilities, most constraints caused by machines and equipment are known to operators and supervisors, but additional constraints can also be in order entry, scheduling and materials issuing. However, to identify Constraints in supply chains requires a resource assessment tool, which is the Supply Chains Network Design Map. This critical supply chains document highlights the Nodes and Links, Flows and resources through each supply chain, with potential Constraints identified within three types:

Flow Constraints

- Demand Constraints: permissible backorders and order-splitting

- Supply Constraints: capacity available and order minimums/maximums

- Transport Constraints: inbound and outbound transport calendars, multi-modal handling constraints; vehicle/route limitations, vehicle/item limitations, vehicle delivery limitations; load/route consolidation rules

Production Constraints: multi-stage production restrictions, minimum order size, min/max batch sizes, equipment capacities, working days and hours; availability of specific skills

Storage Constraints

- Storage Constraints: facility and zone capacities; required safety stocks; dedicated or flexible storage capabilities

- Materials Handling Constraints: at any facility, including receiving, holding and delivery capabilities

When your organisation’s supply chains network has been initially mapped, identify the potential constraints within the process that cannot meet the required ‘takt time’.

- Takt time is the available time (hours, days, weeks) between starting work on one piece and starting on the next. This includes all delays

- Cycle time is the average time it takes to finish one piece

An example notes that if Sales requires 10,000 items per year and the operation runs 250 days per year, the output is 40 items per day, with a takt time of 36 minutes per item. If a Tier1 supplier cannot deliver a part to ensure achieving the production target, they are the CCR, although there could be an unknown constraint within the supplier’s supply chains. A note is required in the Supply Chains Map concerning the CCR’s level of importance to the business and the likely time before scarcity occurs.

How Constraint Management works

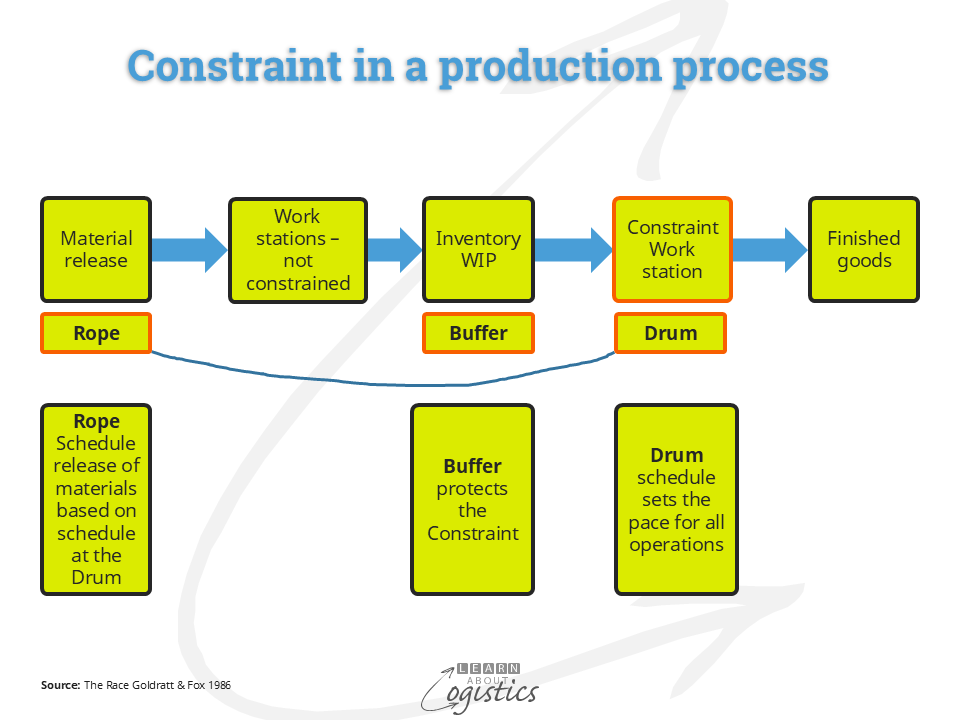

The diagram illustrates a production line, where the Constraint is a production work station with the lowest throughput. This is the CCR or Drum, which dictates throughput for the total process, so the CCR must be utilised to its maximum.

The schedules for other elements of an operation are based on the CCR capacity. The required output, based on sales orders and/or inventory requirements, is evaluated against the CCR and where sufficient capacity is available, the MRP suggested work orders are accepted. The release of orders and materials to the operation (the Rope) must be at the same rate that the Drum is scheduled. This can result in parts of a process or a machine being idle at planned occasions (that is, under-utilised). As Goldratt et al stated in The Goal (1984) “an hour lost at the bottleneck is lost forever and an hour saved at a non-bottleneck is a mirage”.

A buffer of inventory (or time if a non-physical process) is kept behind the Drum. To ensure the Buffer is maintained, upstream work centres are back-scheduled (using finite scheduling) from the CCR. This sequence is called drum-buffer-rope (DBR).

Reduce Constraints

With the CCR identified, an improvement program must be undertaken to identify how the Constraint can be removed. When that occurs, another part of the system will become the constraint and the CCR improvement process is repeated.

Initially, any improvement to buffers in the process will be a near immediate response. Internally, trained operator(s) (who can be permanent part time) must be available to keep the CCR operating through breaks for rest and meals. While eliminating waste through reducing machine changeover times is a benefit, do not add upstream capacity or increase throughput with automation, as it makes the Constraint worse.

If the constraint is with a Tier 1 supplier that is unable to meet the demand, work with the supplier (if possible) to resolve their issues. Also, provide a buffer with increased inventory of inbound items. If a customer has a record of being unable to accept delivery of their order due to limitations of warehouse space or sufficient people to unload the delivery, they are a Constraint.

Longer term internal actions can require installing machines for additional capacity. For external constraints, there is an option to change the design of products and supply chains to reduce exposure to constraints. Another action can be to change from single sourcing and diversify suppliers for critical inputs, with (say) an 70-30 percent split between two suppliers. But, finding a new supplier can require a lot of time and effort. As an indication of the challenge, the Atlanta Federal Reserve in the US identified that after the 2018-19 imposition of tariffs on China, US businesses that switched suppliers to another country took, on average, more than 2.5 years to establish new supplier relationships. The estimated search costs associated with changing suppliers was about U$1.9m per business.

Constraint Management can be difficult to implement, because DBR is opposite to management learning and traditional cost accounting that all machine and labour resources must have maximum utilization. Therefore, the major change required is for scheduling decisions to be based on data about throughput rather than cost. In the wider supply chains network is the challenge to identify and address the root cause behind Constraints. This will require supply chain professionals to use risk management processes to analyse geopolitical tensions and threats from climate change.